Historic Sites of the California Supreme Court

© By Jake Dear* and Levin†

For most of the 20th Century, the California Supreme Court has been headquartered in San Francisco’s picturesque Civic Center Plaza. But such relative stability contrasts sharply with the court’s first 75 years, a period in which the court was forced to relocate at least 18 times. During that early period, politics and natural disasters combined to create an itinerant court, as explained in the brief history that follows.

In February 1850, seven months before Statehood, the California Legislature authorized the Clerk of the California Supreme Court to “rent a suitable room” in San Francisco to hold its March 1850 term. Quarters were not to exceed $1,000 per month, and the clerk was permitted to expend sums necessary for “furniture, stationery, and fuel,” from the general fund.[1]

The Daily Alta California reported on February 27, 1850 that “Mr. Thorpe, Clerk of the Assembly at San Jose, having received the appointment of Clerk of the Supreme Court . . . has arrived in town to perform the duties of his new office.” [2]

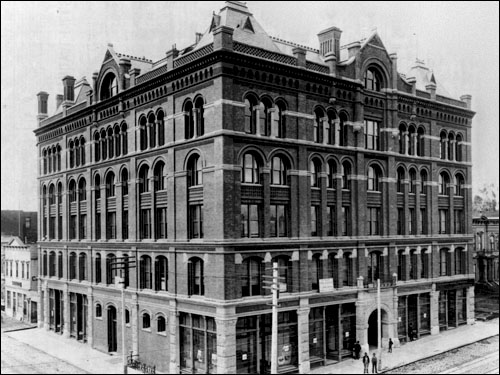

1. Kearny Street at Pacific Avenue (1850-1851) (California Historical Society, FN-31785.)

The next day Thorpe purchased court supplies, including “1 large Journal full bound,” “4 bottles red ink,” “1 bottle black ink,” “3 gross Gillett’s pens,” “1 Parallel Ruler,” “6 Gold pens,” “12 sheets blotting paper,” “1 doz. Pencils,” “24 sticks red tape,” “6 stamps,” “6 Reams fine blue linen cap” paper, and “2 Hydrostatic Inkstands.” [3]

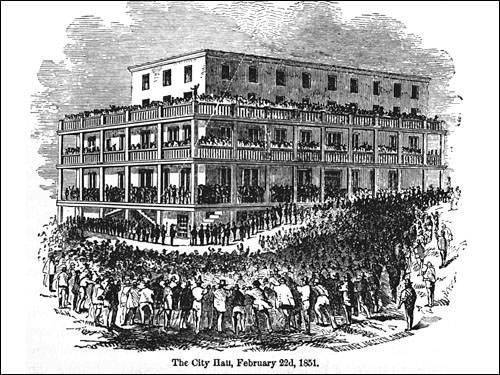

On Saturday, March 2, Thorpe paid the Graham Gray Co. $1,000 for court accommodations for the month, [4] and on Monday the 4th of March, the court “organized” itself [5] in the multi-storied “Graham House” — formerly a hotel, and soon also to house San Francisco City Hall — on the northeast corner of Kearny Street at Pacific Avenue. [6]

The next year, the Legislature directed the court to hold its terms in San Francisco until January 1, 1852, and thereafter “at the seat of Government.” It also specified: “If a room in which to hold the Court be not provided by the State, . . . suitable and sufficient for the transaction of business, the Court may direct the Sheriff of the County in which it is held, to provide such room [and necessities], and the expense thereof shall be paid out of the State Treasury.” [7]

But California’s “seat of government” proved as troublesome to the court as to the rest of government. San José, Vallejo, Benicia, Sacramento and San Francisco vied for the honor of State Capital, and each succeeded for a time. [8] The Constitution decreed that, until changed by two-thirds vote, the Pueblo de San Jose was the “permanent seat of government.” [9] The debates at the first Constitutional Convention in Monterey were robust on the issue and few were mollified by the outcome. [10]

At one point, the court ordered the sheriff of Solano County to provide it with rooms at Vallejo, but this never happened. [11] Instead, “[b]y a joint resolution the Legislature of 1852 . . . resolved that the Supreme Court be authorized to hold its present term in San Francisco and that the Act of 1851, so far as it conflicted with the joint resolutions, be repealed.” [12] Thereafter, the Legislature directed the court to hold its sessions in San Francisco. [13]

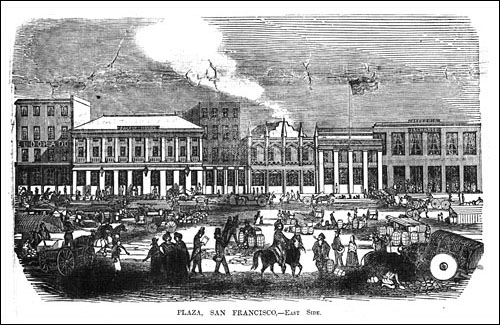

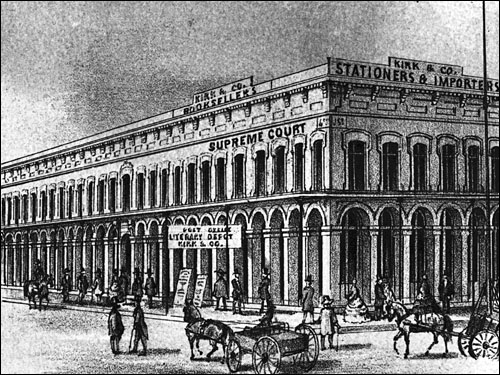

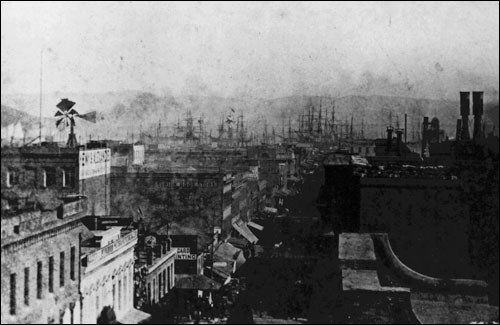

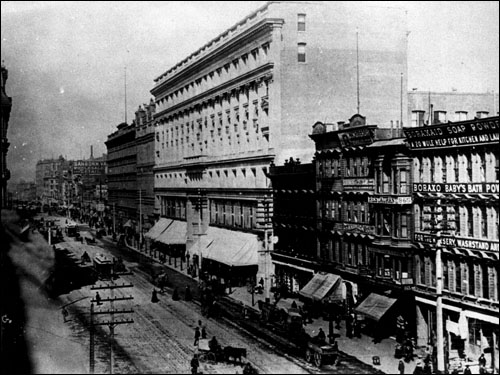

2. ‘California Exchange’ Building, Kearny Street at Clay Street (1852-1853) The San Francisco Directory for September 1852 lists the Court as sharing the San Francisco City ‘Council Chamber’ on the first floor of the ‘California Exchange’ building — to the right of this view — on the northeast corner of Kearny Street at Clay Street. (California Historical Society, FN-04209.)

Because one of numerous and frequent citywide fires had destroyed the first City Hall, [14] the court moved, along with some key parts of city government, to the “California Exchange” [15] building on the northeast corner of Kearny at Clay Street (image 2), where, according to the San Francisco Directory for September 1852, [16] it had offices on the first floor (room No. 4, the “council chamber”).

Tired of paying high rents for its offices, the City of San Francisco decided to purchase its own building. Meanwhile, at the center of Portsmouth Square on Kearny Street, the Jenny Lind Theater had fallen on hard times and was for sale. (The theater had been named for the famed “Swedish Nightingale” in an attempt to induce her to visit San Francisco — but she never did so.) When the City attempted to purchase the theater in 1852, taxpayers sued, claiming the purchase was illegal. After extensive litigation the Supreme Court held the purchase to be proper. [17]

Presumably, the theater’s saloon, four billiard tables, and six bowling alleys [18] were removed to make room for offices. Within months of the court’s decision, the court moved — along with much of city government — into the refurbished building. [19] (image 3) The basic character of the neighborhood was little changed, however: next door remained the infamous El Dorado saloon, “a free-wheeling den of iniquity that catered to a not-altogether-reputable clientele.” [20]

3. Kearny Street at Portsmouth Square (1853-1854) The Court was located in the centered building, which also house San Francisco’s City Hall. (Copy of original by G.R. Fardon, California Historical Society, FN-29364.)

In 1854 the Legislature settled on Sacramento as the “seat of Government,” [21] and on March 24, it specified “the sessions of the Supreme Court shall be held at the Capital of the State.” [22] “But by this time the executive and judicial branches . . . had become so bewildered that the latter refused to obey . . . and sat instead at San Francisco, wither it had been ordered in 1850 to betake itself.” [23] On March 27, the court in chambers voted 2-1 that San José, and not Sacramento, was the capital. [24] The court ordered the

“Sheriff of Santa Clara County [to] procure in the town of San José and properly arrange & furnish a Court room, Clerk’s office & consultation room for the use of this Court.

It is further ordered, That the Clerk of this Court forthwith remove the records of the Court to the town of San José.

It is further ordered that the Court will meet to deliver opinions at San José on the first Monday in April, & on that day will appoint some future day of the term for the argument of cases.” [25]

The March 31, 1854, Daily Alta of California contained this notice: “Departure of the Supreme Court — The archives, and a portion of the furniture of the Supreme Court, accompanied by the Clerk, took their departure yesterday for San José, in accordance with the decision recently rendered by the majority of the court. The court went off in a style in keeping with its supremacy. A handsome Express wagon of Messrs. Adams & Co., to which were harnessed the private horses of the proprietors, drew up before the door of the City Hall, and received the legal lore, handsomely bound, which has been accumulating in the Court since its organization. The Court went off in dashing style, and we fancied that we saw the shades of Blackstone and Coke looking out of one of the windows of the City Hall. . . .” [26]

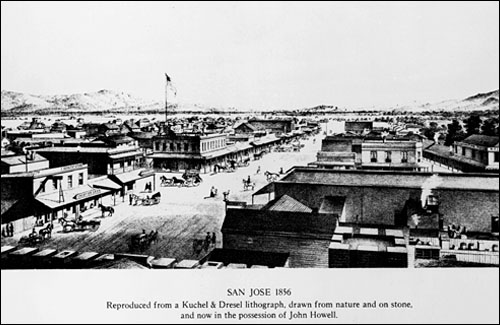

4. San José (1854) The Court was located on the second story of the brick structure at the corner of Pacheco and Santa Clara Streets, directly across from the Washington Hotel, on the right side of this view.

The San Jose Telegraph reported that “Sheriff McCutchan . . . has provided the large and very handsome hall, in the second story of the new and substantial brick building, at the corner of Pacheco and Santa Clara Streets, for the use of the Supreme Court. (image 4) A very neat room, suitable for the Clerk’s office opens into the hall. The Supreme Court will be quite elegantly and conveniently provided for here, as at any place in the State. The rooms, and the location, fit exactly.” A week later the Telegraph noted that “[a] full bench convened on Monday last in the tastefully furnished rooms provided by the sheriff to the Supreme Court. . . .” [27] Thereafter, the Telegraph reported the Supreme Court “will hold its sessions in this city — the attempt to remove it by the Legislature having failed. The Legislature and officers of the State will remain at Sacramento next winter and then where — who knows? We are satisfied and gratified to have the Supreme Court with us. . . .” [28]

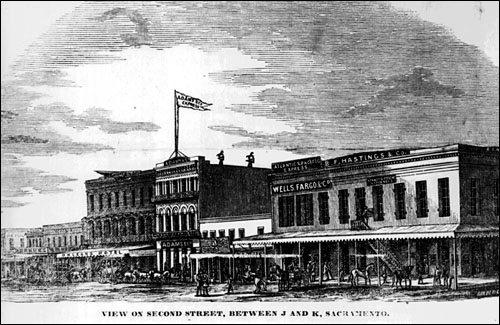

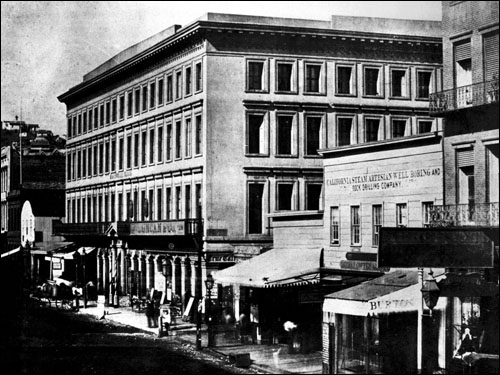

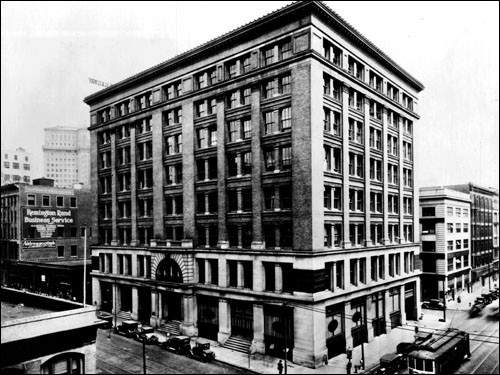

5. B.F. Hastings Building — 2nd Street, between J and K Streets, Sacramento (1855-1857; 1859-1862; 1862-1869)

“To settle these vexed questions [concerning the seat of government] a special term of the supreme court was ordered to be held at Benicia, in January 1855, at which time the Legislature would be in session.” [29] But before that could occur, the court heard another case presenting a renewed challenge to its earlier determination concerning the site of the state capital. While that case was making its way to through the court, Justice Alexander Wells — who lived in San José and who had earlier been in the majority that held San José to be the state capital — died and was replaced by Justice Charles H. Bryan, who promptly voted with Chief Justice Hugh C. Murray and authored an opinion holding Sacramento to be the lawful capital. [30] The court immediately moved to Sacramento, where it took up residence on the second floor of the B.F. Hastings Building (Second and J Streets) in what is now Old Sacramento. [31] (image 5) In 1863, when the number of justices was increased from three to five, the clerk of the court was forced to move his offices to the first floor. [32] The building still stands, and in February 2000 the court held therein a special oral argument session commemorating the court’s sesquicentennial. [33]

6. Jansen Building, 4th & J Streets, Sacramento (1857-1859)

7. K Street, looking east from 4th Street during the flood of 1862, Sacramento

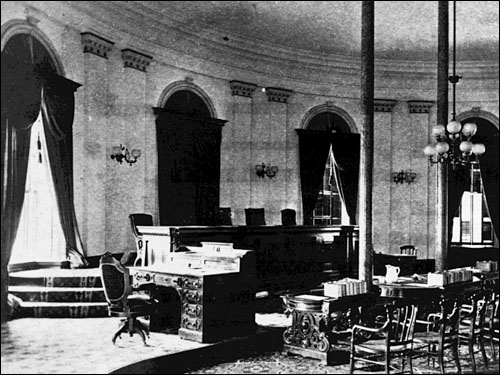

1857, the court moved a few blocks to the Jansen Building at 4th & J Streets, which it shared with the State Library [34] where it had offices on the second floor. [35] (image 6) The court returned to the Hastings Building in late 1859, until it was apparently evicted in January 1862 by the great flood. [36] (image 7) Thereafter the court again returned to the Hastings site. It remained there until moving to the east wing apse of the capitol building in late 1869, [37] (image 8) where it again shared space with the State Library. [38] The Sacramento Union of December 4, 1869, reported: “The new Supreme Court room at the Capitol was used yesterday afternoon for the first time, Judge Sanderson hearing the habeas corpus case of Nellie Smith and Anna Keating” in a case challenging the validity of a city ordinance barring women from being in a drinking saloon after midnight. [39]

8. Courtroom in Capitol Building, Sacramento (1869-1874)

9. Clay Street (1874-1878. 1878-1881) The Court was located at 640 Clay Street — on the left (north) side of this view, most likely in (or to the bay side of) the ‘Union Book Store’ building.

With the adoption of the codes in 1872, the Legislature decreed the justices and court personnel must “reside at and keep their offices in the City of Sacramento.” [40] In early 1874, however, the court began keeping offices and holding many of its regular sessions in San Francisco, at 640 Clay Street. [41](image 9) That same year the Legislature validated the practice, permitting the court to sit in San Francisco for its January and July terms, provided that the San Francisco Board of Supervisors procured and paid for sufficient accommodations. [42] In 1878 the Legislature further expanded the court’s oral argument schedule, providing that the court should hold sessions in Sacramento, San Francisco, and Los Angeles [43] — a practice that continues to this day. The court conducted its first session in Los Angeles on October 14, 1878, in the “Hellman-Mascrel Block.” [44]

The impetus for the movement of the court’s headquarters from Sacramento is unclear, but it appears that weather, water and whisky had a lot to do with it. When the delegates to the 1879 Constitutional Convention considered proposals to require the court to hear all sessions “at the Capital of the State,” the relative positions of the Sacramento, Los Angeles, and San Francisco sites were strongly contested.

In favor of Sacramento it was argued that the court should sit at the seat of government. Opponents claimed that Sacramento had the highest death rate of any city of its size in the world, and its climate and whisky was bad. [45]

Other delegates asserted that the court should at least regularly hold sessions at Los Angeles, because that city — a “great community composed of agriculturalists” [46] — was bound to grow in size and stature [47] and was “about the only place in the State where you can get wine that is not adulterated.” [48] But it also was said that “the climate down there is very hot, and a man soon gets lazy who lives in it. . . . And it would not be very long, if you have the Supreme Court down there, before you would see the Chief Justice, and . . . General Howard [a proponent of Los Angeles], walking arm in arm under huge Panama hats, hunting a cool place. It will not do.” [49]

10. The Montgomery Block (1878)

11. Stockton Street (1881-1883) The Court was located at 105 Stockton Street in the ‘Wakelee Building,’ on the west side of the street (right side of this view, in or near the five-floor structure with the large signage on its side).

Champions of San Francisco asserted that it was the center of commerce, and its weather was superior to that of Sacramento, which was prone to flooding and excessive heat: “The Judges will be seen some of these days coming out of the Court-room in a boat. . . . I have had some little experience with this climate myself. It is the hottest place outside of — the one down below that we read of. . . . If you put it in the Constitution that the Court shall sit . . . here in regular session all Summer, they will have to be regular salamanders.” [50] On the other hand, it was observed “earthquakes have shaken San Francisco from center to circumference . . . . Suppose an earthquake were to destroy that city . . . ?” [51]

Ultimately, the drafters of the new Constitution left the question open, and the court continued to use 640 Clay Street in San Francisco as its headquarters, and continued to hear oral argument at that site as well as in Sacramento and Los Angeles.

12. Post Street, looking west from Kearny Street to Grant Avenue (1883-1890) The Court was located in the left (south) block, number 121, in the building immediately below the ‘Frey’s Music Store’ sign.

13. 305 Larkin Street at McAllister Street (1890-1896)

Although the court is reported to have been located for a short time in 1878 on the “Montgomery Block,” [52] (image 10) the court apparently returned to 640 Clay until at least 1881, when it moved to the Wakelee Building at 105 Stockton Street, near O’Farrell (image 11), where it stayed until 1883. In 1884 the court moved to 121 Post Street (image 12), where it kept offices until 1890. From there the court moved to 305 Larkin Street at McAllister — site of the present court building — to a handsome structure called the “Supreme Court Building” (also known as the “Hale Building”) (image 13), where it stayed until 1896, when it moved to the “Parrott Building,” at 825 Market Street (also known as the “Emporium”) (image 14). The court was located here during the 1906 earthquake, which destroyed its offices, many records, and most of the court’s library (image 15). [53]

14. The Emporium Building, 825 Market Street (1896-1906)

15. The Emporium Building entrance after the earthquake and fire.

Immediately after the quake and fire the court moved to the “Century Club Building” at 1355 Franklin Street (image 16), a then-new structure that had survived the post-quake fires, which were generally stopped at Van Ness (image 17). The Club (a private women’s social organization) negotiated a rent of $625 per month — an increase of $25 over the court’s initial proposal. [54] In August 1907, the court moved to the “Central Building,” 1214 Polk Street at Sutter. [55] (image 18) By the beginning of 1908, the court moved to the eighth floor of the “Wells Fargo Building” (later the “Pacific Telephone Building”), 85 Second Street at Mission (image 19), where it remained until 1923 — a then record 15 years in one location.

16. 1355 Franklin Street (1906-1907)

18. 1214 Polk Street (1907) The Court briefly occupied the Central Building at 1214 Polk Street (near Sutter Street), five blocks up in this view, on the right (a light-hued three-floor building)

17. Franklin Street, looking north from Sutter Street (1906)

19. The Wells Fargo Building, 85 Second Street at Mission Street (1908-1923)

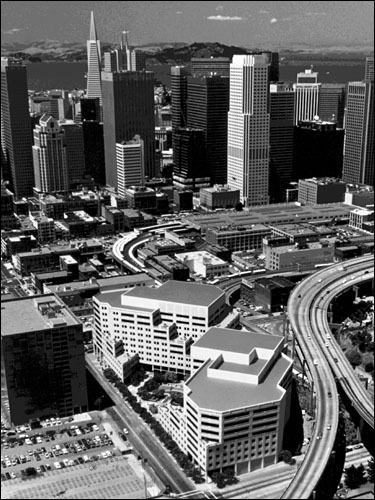

The court moved that year for the first time into its present quarters — the State Building, located at 350 McAllister Street. (image 20) The building was the product of a design competition in which the plans of eight finalists were reviewed and judged by a committee of architects and laypersons. [56] The court remained at this site despite efforts in the 1920s to induce its return to Sacramento, to take up residence in the then-newly constructed Library and Courts Building. [57]

20. State Building, 350 McAllister Street (1923-1989, 1999-present)

21. 455 Golden Gate Avenue (1989-1991)

In the early 1950s the original courtroom on the fourth floor of the McAllister Street building was revised and modeled in part on the United Nations Security Council chamber. The court remained at the McAllister site for 66 years, until October 1989, when the building — already scheduled for seismic retrofitting — suffered substantial damage in the Loma Prieta earthquake. Stairwell walls buckled, bookcases “pitched out their heavy contents,” and an enormous bronze ceiling light fixture crashed down on the floor near Chief Justice Lucas’s desk. [58] The court moved immediately into the drab 1950s era quarters of the Administrative Office of the Courts on the fourth and fifth floors of 455 Golden Gate Avenue (image 21), a building adjacent to and connected with 350 McAllister Street. [59] The court stayed there until early 1991, and during this time held oral argument sessions in the hearing room of the Public Utilities Commission, located at 505 Van Ness Avenue at McAllister.

22. 303 Second Street (1991-1999)

In early 1991 the court moved to the eighth and ninth floors of 303 Second Street. [60] high-ceilinged and dark-wood paneled chamber, was located on the fourth floor.

Finally, in early 1999 renovation of 350 McAllister Street was completed and the court returned — moving for at least the 22nd time in its 150 year history — to the Earl Warren Building. (images 23 & 24) The courtroom, which was dedicated on January 8, 1999, was remodeled in a fashion more in keeping with its original design. The court occupies the fourth through sixth floors, and has clerk’s offices and related personnel on the first floor. [61]

The well-traveled California Supreme Court is now firmly rooted and continues serving the People from its “historic” home.

23. 350 McAllister Street (Earl Warren Building), State Building Complex. Construction of the Hiram Johnson component (455 Golden Gate Avenue) of the State Building complex is shown in the background.

24. 350 McAllister Street (Earl Warren Building), State Building Complex (1999-present)

Article originally published in Jake Dear and Levin, Historic Sites of the California Supreme Court, 4 Cal. Sup. Ct. Hist. Soc’y Y.B. 63 (1998-99)

* Senior Staff Attorney, Chambers of Chief Justice Ronald M. George, California Supreme Court.

† Senior Staff Attorney, Chambers of Justice Fred K. Morrison, Third District Court of Appeal.

Footnotes:

[1] Stats. 1850, ch. 22, § § 1 & 2, pp. 76-77.

[2] Feb. 27, 1850, p. 2, col. 2.

[3] Controller Claim Schedules, 3901:314-1, California State Archives, Office of the Secretary of State, Sacramento.

[4] Ibid., 3901: 254-1. The charge, $1,000, covered “1 Month Rent of Court Room, Clerk’s Room and Consulting Room from March 2 to April 2” ($900) and “Fuel for Lights 1 month” ($100). (Id., 3901:254-2.)

[5] The Court’s first entry in its Minute Book, in handwritten script, reads: “Supreme Court of the State of California/ San Francisco, March 4th 1850./ Court organized San Francisco — present their Honors Nathaniel Bennett & Lyons, associate Justices & E.W. Thorpe, Clerk.” (Supreme Court Minute Book “A,” California State Archives, Office of the Secretary of State, Sacramento.) The court adjourned until the next day, when it met and adjourned again. On its third day of business, March 6, 1850, the court granted the first application to practice law. Chief Justice Serranus Clinton Hastings arrived at the court and assumed his duties on Thursday, March 7. Most of the court’s work during its first few weeks consisted of granting applications to practice law. (Ibid.)

[6] The state of the law, and the judicial system, was then in flux. (See, e.g., Kroninger, The Court’s First Year: Colorful and Chaotic (1994) 1 Cal. Sup. Ct. Hist. Soc. Yearbook 139, 140.) In the first case decided by the court, People v. Smith (1850) 1 Cal. 9, the court concluded that certain prisoners had been properly arrested and detained but the court nevertheless discharged them, explaining: “[C]onsidering the want of definite and well understood laws regulating proceedings in the existing courts of First Instance, and the uncertainty as to the time when the district courts will be ready to proceed with business, superadded to the fact that there is no jail or prison in which prisoners can be kept with security, we feel disposed to order their release upon bail.” (Id., at pp. 14-15.)

[7] Stats. 1851, ch.1, § 14, p.11.

[8] E. D. Wilson, California’s Legislature (1994) pp. 137-144 (Wilson); O. K. McMurray, An Historical Sketch of the Supreme Court of California, published in Historical and Contemporary Review of Bench and Bar in California (S. F. Daily Journal 1926), 22, 28 (McMurray); C. Goodwin, Establishment of State Government in California (1914) pp 306-307, fn. 1.

[9] Cal. Const. of 1849, art. XI, § 1.

[10] See J. R. Browne, Report of the Debates in the Convention of California (1850) pp. 239-246, 362 [many places for court location proposed].

[11] McMurray, supra, at p. 28.

[12] Id.; see Stats. 1852, p. 286.

[13] Stats. 1852, ch. 86, p. 162; Stats. 1853, ch. 180, sub-ch. II, § 11, p. 289.

[14] The court’s opinion in Elliott v. Osborne (1851) 1 Cal. 396, issued May 28, 1850 (Supreme Court Minute Book “A,” California State Archives, Office of the Secretary of State, p. 347), begins: “The papers in this cause were destroyed by the late fire, and we must rely upon our recollection of the facts, as presented on the argument.” Likewise, Chief Justice Hastings’ separate statement in Weber v. The City of San Francisco (1851) 1 Cal. 455, 458, issued July 19, 1850 (Supreme Court Minute Book “A,” supra, pp. 434-435) refers to recent “fires,” which apparently included the conflagration of June 22, 1851, which destroyed the first City Hall building. (See F. Soule (1855) Annals of San Francisco, pp. 345, 611-613 (Soule).)

[15] It is unclear whether the court moved directly to that site from the fire-destroyed City Hall, or whether it first took temporary quarters elsewhere.

[16] Id., at pp. 68-69. With the exception of the court’s reported (and apparently brief) stay at the “Montgomery Block” in 1878, all subsequent San Francisco locations of the court described herein through 923 have been confirmed in the relevant San Francisco City Directories.

[17] De Witt v. San Francisco (1852) 2 Cal. 289.

[18] Daily Alta California, June 10, 1851, p. 2, col. 3.

[19] Soule, supra, at pp. 353-354.

[20] San Francisco Album [of] George Robinson Fardon (1856) (1999 ed. [Fraenkel Gallery, et al., San Francisco]) at p. 150.

[21] Stats. 1854, ch. 9, § 1, p. 21.

[22] Stats. 1854, ch. 14, § 1, p. 25.

[23] VI Bancroft, History of California (1888) p. 323 (Bancroft).

[24] See W. Willis, History of Sacramento County (1913) p. 360 [asserting the Supreme Court “retaliated by holding the opinion that San Jose was the constitutional and legal capital and refused to come.”].

[25] California State Archives, Supreme Court Minute Book “C,” p. 220 (order of Heydenfeldt & Wells, JJ.); see also F. Hall, The History of San José (1871) pp. 265-267.

[26] San Jose Telegraph, March 30, 1854, at p. 2, col. 3.

[27] Id., April 6, 1854.

[28] Id., May 18, 1854.

[29] Bancroft, supra, at p. 324.

[30] People ex rel. Vermule v. Bigler (1855) 5 Cal. 23. This decision was perhaps Justice Bryan’s most significant during his brief tenure on the Court; within one year, he was defeated by David S. Terry, running on the “Know-Nothing” ticket. (See Miller, The Search for Justice Bryan (1996-1997) 3 Cal. Sup. Ct. Hist. Soc. Yearbook 147, 148.)

[31] See T. Severson, Sacramento, An Illustrated History: 1839 to 1874 (Cal. Hist. Soc. 1973), p. 190 (Severson). The court’s time at this site was certainly eventful, though not always decorous. For example, in 1857, California’s pro-slavery Governor, Neely Johnson, sent Supreme Court Justice David Terry as his emissary to defuse the vigilantes in San Francisco. Soon after arriving to undertake his delicate diplomatic mission in the city, Justice Terry found himself in a situation in which he felt compelled to plunge his bowie knife into the neck of one Hopkins, a vigilante member. The vigilantes arrested Terry and imprisoned him for six weeks, during which time Hawkins miraculously, and to the relief of all, recovered. The vigilantes tried Terry for lesser crimes, convicted him, and then released him. When Terry returned to the courtroom from his imprisonment, he was greeted by a six-week backlog of work. During his absence, one of the other three justices — Heydenfeldt — had been out of state, in Europe. Because there had been no quorum during Terry’s absence, the sole remaining justice — Chief Justice Murray — was left to amble about the court’s chambers by himself, and in effect, the court was shut down during this time. (The story is recounted in detail in M. Gould, A Cast of Hawks (1985) at pp. 57-69; see also A. Roth, The California State Supreme Court, 1860-1879: A Legal History (University Microfilms, 1973) at p. 10.)

The court’s justices apparently set the tone for conduct of its staff, as demonstrated by the story of the court’s seventh reporter of decisions, Harvey Lee. Unlike his predecessors, Lee was appointed not by the court, but by the Legislature. The court was not very happy with this new arrangement, and there was some concern that Lee was not up to the job. Justice Steven Field later commented that Lee’s work was ” Ôso defective that an effort was made by the judges to get the [new] law repealed’ ” and have the appointing authority returned to the court. (McMurray, supra, at p. 30.) As explained in McMurray, supra: “This lead to a bitter feeling on [Lee’s] part toward the judges, and in a conversation with Mr. Fairfax, the clerk of the court, [Lee] gave vent to it in violent rage. Fairfax resented the attack, an altercation ensued, and Lee, who carried a sword cane, drew his sword and ran it into Fairfax’s body, inflicting a serious wound in the chest just above the heart. A second wound, not so serious as the first, followed, and Fairfax drew his pistol as Lee raised his sword for a third thrust. He was about to shoot, but restrained by the thought of Lee’s wife and children, let the pistol drop.” (Ibid Evidently, this was widely circulated news, and ” ‘All California rang with the story of this heroic act.’ ” (Ibid)

[32] B.F. Hastings Building (Pamp.), Cal. Dept. of Parks & Rec.

[33] See Celebration of the 150th Anniversary of the Supreme Court, 22 Cal.4th 1259 et seq.

[34] The inadequacy of library space in the Hastings Building was a major factor motivating the move. As explained in a March 2, 1858, letter from Justices David S. Terry and Peter H. Burnett to the State Controller, the court required a special appropriation of “about $1,500” to move to the Jansen Building due to the “want of proper accommodations in the building formerly occupied, the room used as a State Library being entirely unfit for such purposes.” (Controller files, F3617:130 (1852-1906), California State Archives, Office of the Secretary of State, Sacramento.) The court expended $583 for “moving and fitting up the Library,” $250 for moving the court’s furniture and for related carpentry, $330 for carpeting, $242.25 for upholstery, and $109.75 for “Stoves, etc.” (Ibid.)

[35] See Sacramento Bee (Jan. 18, 1860) [The Jansen Building, “lately occupied by the supreme court, will soon be used as the county courthouse . . . . The late state library room will be the district courtroom and the court of sessions will meet where the supreme court did”]; see also Wilson, supra, at p. 146 [discussing destruction of the apse during remodeling of 1949-1952].

[36] See McMurray, supra, at page 29. It is unclear where the court was located immediately after the flood, or, indeed, whether it remained in Sacramento during that time. We note that because of the flood, the Legislature temporarily departed Sacramento for San Francisco, where it remained from late January to mid-May 1862. (See Wilson, supra, at p. 143 [“The business of the state resumed in the Merchants’ Exchange Building, which stood on the northeast corner of Battery and Washington Streets”]; Bancroft, supra, at p. 325 [“the great flood forced everybody out of Sacramento who could go”]; IV Hittell, History of California (1898) pp. 294-295; Brady, Flood Sends Capital to City (July 31, 1990) San Francisco Independent, p. 14B.) At least one thoughtful researcher has concluded that the court did not move from Sacramento in 1862. (See L. Schei, Sacramento and the Supreme Court, Sacramento Lawyer (March 2000) at p. 28.)

[37] Severson, supra, at p. 196 [“[T]he court beat the legislature in occupying the capitol by days”]; Willis, History of Sacramento County, supra, at p. 362.

[38] This linkage continues today in the State Library and Courts Building in Sacramento, completed in 1929, which houses both the State Library and a courtroom used semi-annually by the Supreme Court, and by the Third District Court of Appeal during the rest of the year.

[39] See Ex Parte Smith and Keating (1869) 38 Cal. 702 (and reporter’s note) [upholding the ordinance].

[40] Former Pol. Code, § 852.

[41] See McMurray, supra at p. 29. In early 1879, a delegate to the Constitutional Convention observed, “it is well known that until four or five years ago the Supreme Court was permanently located [in Sacramento].” (II Willis & Stockton, Debates and Proceedings of the Constitutional Convention of the State of California (1880) & (1881), at p. 953 (Willis & Stockton).)

[42] Acts Amendatory of the Codes, 1873-1874, ch. 675, § 1, pp. 395-396 (former Code Civ. Proc., § 50).

[43] Acts Amendatory of the Codes, 1877-1878, ch. 142, § 2, p. 22 (former Code Civ. Proc., § 50).

[44] McMurray, supra at p. 29; Sacramento Union Oct. 17, 1878, p. 2.

[45] Willis & Stockton, supra, at pp. 952, 953, 955. In response, it was suggested that those who objected to Sacramento did so for reasons of personal interest: “Now, my colleague, Senator Herrington, . . . speaks of this as being a very unhealthy place; he speaks of the extensive graveyards, . . . and vilifies Sacramento to an extent which I think is not warranted. I can account for that. The gentleman has made some effort to get into good society here, and has been barred out, because I know the people of Sacramento are a very kindly people, as I have found out, especially the ladies. I think what hurts my colleague, is the fact that the ladies of Sacramento have failed to appreciate him, and notice him.” (Id., at p. 956.)

[46] Id., at p. 955.

[47] Id., at p. 952.

[48] Id., at p. 953.

[49] Id., at p. 953.

[50] Id., at p. 953; see also id., at p. 952 [asserting that Sacramento is “the most unhealthy spot in the State of California. I think the river will drown out this city.”]; id at p. 953 [stating that “a vulture could not fly over the City of Sacramento without dropping dead in his flight”].

[51] Ibid.

[52] McMurray, supra, at p. 29.

[53] Ibid.

[54] (September 1999 Telephone interview with Virginia Gibbons, Century Club Historian.) While at this address, the court accepted n offer from the Bancroft-Whitney Co. to replace numerous library books lost in the earthquake and fire at “special fire prices” and “upon the basis of their cost . . . plus a commission of 10%,” all “to be paid for when the library gets funds again.” (Letter from Bancroft-Whitney Co. to Benj. Edson, July 28, 1906.)

[55] Some correspondence lists an address of “Sutter and Larkin.”

[56] See B.J.S. Cahill, Plans for the State Building on the San Francisco Civic Center (1917) 58 The Architect and Engineer of California 39-62 [reproducing and critiquing the eight proposed designs].

[57] The story is told with partisan flair in Regnery, The Capitol Extension Group (July 1984) 8 California State Library Foundation Bulletin 1, 7-8.

[58] See Courtroom Dedication (1999) 19 Cal.4th 1281, 1285 (comments of Lucas, former C.J); 1283 (comments of George, C.J.). As former Chief Justice Lucas explained, “[t]he building was in such a potentially dangerous condition that we could only allow court members and staff to go separately and individually into the building to get their personal possessions, and for no more than 10 minutes.” (Id., at p. 1285.)

[59] As former Chief Justice Lucas explained, so “began a long a dreary period for all of the staff and members of the Court. For 16 months . . . we were in Limbo . . . , working in the old State Building on Golden Gate . . . , haggard and aged well beyond its years. Ultimately it was torn down to make way for this new complex, and not a minute too soon.” (Courtroom Dedication, supra, 19 Cal.4th 1281, 1285.)

[60] This move triggered an unusual disqualification of the California Supreme Court in a dispute concerning its new landlord. Justices of the Third District Court of Appeal were chosen to decide the case. (See Carma Developers (Cal.), Inc. v. Marathon Development California, Inc. (1992) 2 Cal.4th 342, 350, fn. 1.)

[61] The Supreme Court shares the Judicial Center Library — located on the fourth floor of the Hiram Johnson Building, 455 Golden Gate Avenue — with the First District Court of Appeal. Four of the five divisions of the court of appeal, and that court’s clerk’s office, occupy the third, second, and part of the first floor of the Earl Warren Building. The fifth division of the First District Court of Appeal is located adjacent to the library,on the fourth floor of the Hiram Johnson Building.