A Short Documentary on the History and Operation of the California Supreme Court ›

History of the California Supreme Court

The history of the California Supreme Court reflects the history of California itself. After a long period of Spanish and Mexican rule, California was occupied by the United States in 1846 during the Mexican-American War. On February 2, 1848, Mexico officially ceded California to the United States in exchange for $15 million. That same year, gold was discovered in California. The tumultuous events of the ensuing Gold Rush shaped many of the issues that would later be decided by the California Supreme Court.

1849 Constitution

In September 1849, 48 delegates assembled at Colton Hall in Monterey to draft the state’s first Constitution, which was completed in six weeks. Article VI of the new Constitution, covering the judicial branch, provided for a Supreme Court consisting of a Chief Justice and two associate justices. The Constitution provided that the first three justices would be elected by the state Legislature and that subsequent justices would be elected by the voters for six-year terms in contested elections.

The First Justices

Serranus Clinton Hastings, the first Chief Justice of California (1850–1852).

In December 1849 the new Legislature elected Serranus Clinton Hastings as California’s first Chief Justice and H. A. Lyons and Nathaniel Bennett as its first associate justices. Hastings, a former Iowa representative to Congress, had resigned his position as chief justice of that state’s supreme court to come to California. After serving on the California Supreme Court, he became state Attorney General and later founded Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco.

In February 1850 the California Legislature authorized the clerk of the California Supreme Court to “rent a suitable room” in San Francisco for the court’s quarters. The chronicles of the day record that the new clerk duly arrived and purchased court supplies including “1 bottle black ink,” “3 gross Gillett’s pens,” and “24 sticks red tape.” On March 4, 1850, the court convened for the first time in the Graham House, a former hotel on the northeast corner of Kearny Street and Pacific Avenue. It was quartered there when California officially joined the Union in September 1850.

Much of the litigation during this early period dealt with the legal concerns of the people who flocked to the state during the Gold Rush. Many of their cases involved titles to property, mining and agricultural issues, and rights to water and minerals on public lands. Often those decisions were not published. In the early years of statehood, the opinions issued by the court filled less than one slim volume of the Official Reports annually.

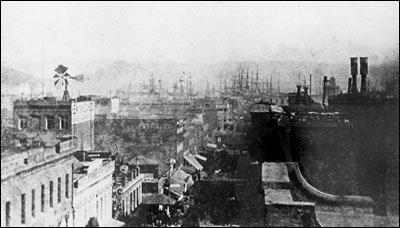

The court was located at 640 Clay Street (left side), San Francisco, from 1874 to 1881. In the background are the masts of ships anchored in the bay.

The Court Grows

The California judiciary was reorganized in 1862 to meet the needs of a growing state. Article VI of the California Constitution was amended to expand the categories of cases the court could hear and to increase the number of Supreme Court justices from three to five. Terms of office were increased from 6 to 10 years.

The Constitution Is Revised

K Street in Sacramento, 1862, rowing east.

In 1877 the people of California voted to hold a state convention to revise the Constitution. The call for a convention grew largely out of the economic upheavals and political controversies of the time. The Workingmen’s Party, a local version of the widespread Granger movement of the 1870s, played a major role in the demand for constitutional change.

California’s population growth—from 100,000 in 1849 to 800,000 in 1877—reflected the state’s new economic circumstances. The gold mining concerns that dominated the first Constitution had given way to agricultural, commercial, and manufacturing interests.

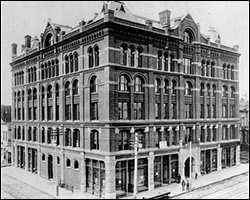

The court was located at 305 Larkin Street, San Francisco, from 1890 to 1896.

The California Legislature responded to the voters’ mandate by passing an enabling act that authorized the election of 152 delegates to meet in Sacramento in September 1878.

When the convention finally adjourned seven months later, in March 1879, major changes had been made to California’s judicial system, which were formalized when the voters adopted a new Constitution in May of that year. The Supreme Court had been expanded again. It was now to consist of a Chief Justice and six associate justices, and terms of office were increased from 10 to 12 years. The categories of cases that the court was authorized to hear were once again augmented, and all opinions were required to be in writing.

A Home for the Court

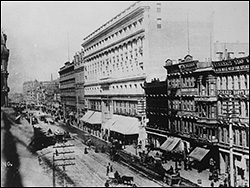

The Emporium Building, 825 Market Street, San Francisco. The court was located here from 1896 to 1906, when it was evicted by the earthquake.

The question of where to hold Supreme Court sessions was a topic of lively debate in early California. The first court convened in San Francisco and remained there until 1854. Subsequently the Legislature mandated the court’s relocation to the state capital, still to be selected. After a separate legislative struggle, Sacramento was finally chosen as the official seat of government, but because the court initially held the Legislature’s selection to be invalid, it spent most of 1854 in San Jose.

The court then moved to Sacramento, but it returned to San Francisco in the early 1870s. By 1874 this fluid arrangement was formalized. The Legislature directed the court to hear oral arguments two months each year in San Francisco and two months each year in Sacramento. In 1878 the Legislature directed the court to hear arguments twice yearly in each of those cities and twice in Los Angeles, as well.

During the 1879 Constitutional Convention, the Judiciary Committee considered the pros and cons of a “court on wheels” holding sessions in different locations. Some delegates opposed the expense and inconvenience of such an arrangement; others debated the relative merits of the water, weather, and whisky of the respective locations. The committee decided to leave the matter unspecified in the Constitution.

Coping With an Increasing Caseload

The court was located in the Wells Fargo Building, 85 Second Street, San Francisco, from 1908 to 1923.

By 1882 the Supreme Court had a backlog of pending cases, with an average wait of two years for a case to be decided. In 1885 the Legislature directed the court to appoint three commissioners to help dispose of the backlog. Two more were added in 1889, but that did not sufficiently alleviate the court’s workload.

In 1904 three Courts of Appeal were created and the commissioners were eliminated. The new courts were to handle all appeals in the “ordinary current of cases,” leaving appeals in the “great and important” cases to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court also was given the power to transfer a case from a Court of Appeal to itself, from itself to a Court of Appeal, and from one Court of Appeal to another. This provision gave the Supreme Court the power to rule on the most important legal questions and to resolve conflicts among the appellate districts.

The court originally moved to its present location at 350 McAllister Street in 1923 and remained until it was temporarily displaced by the earthquake in 1989.

Subsequent Constitutional Amendments

A 1926 amendment to article VI of the Constitution established the Judicial Council of California, chaired by the Chief Justice. The council’s mandate is to improve the administration of justice and to enact rules of court practice and procedure.

The following year, another constitutional amendment created the State Bar, a public corporation to which all attorneys practicing in California must belong. Each year, candidates for admission to practice law are examined by the State Bar, which then certifies to the Supreme Court the applicants who meet admission requirements.

In 1934 noncontested judicial elections were adopted for the appellate courts, including the Supreme Court. Under this system, the Governor, subject to confirmation by the Commission on Judicial Appointments, fills vacancies in the appellate courts by appointment. At the next general election, voters decide whether the appointees should be confirmed to fill their predecessors’ unexpired terms and whether justices whose terms have expired should be elected to new full terms.

Today’s Supreme Court, the Judicial Council of California, and the Administrative Office of the Courts conduct business in the connected Hiram W. Johnson State Office Building (taller structure) and Earl Warren Building (foreground).

Unifying the Trial Courts

In 1998 the California voters amended the Constitution to allow each county’s trial judges to unify their courts, if desired, into a single countywide superior court system. Until then, separate municipal courts in each county had handled the less serious matters, such as misdemeanors, infractions, and minor civil cases. All 58 counties have now consolidated their municipal courts with their respective superior courts. This restructuring has streamlined judicial branch operations statewide, resulting in improved services to the public.

The California Supreme Court justices in the Stanley Mosk Library and Courts Building, Sacramento, July 2006.

Left to right: Associate Justice Carlos R. Moreno, Associate Justice Joyce L. Kennard, Associate Justice Kathryn M. Werdegar, Chief Justice Ronald M. George, Associate Justice Ming W. Chin, Associate Justice Marvin R. Baxter, Associate Justice Carol A. Corrigan.

Source Credit: The text and photos from Part 3 of The Supreme Court of California (2003, 2007 & 2019 eds.) are used by permission of the Supreme Court of California.