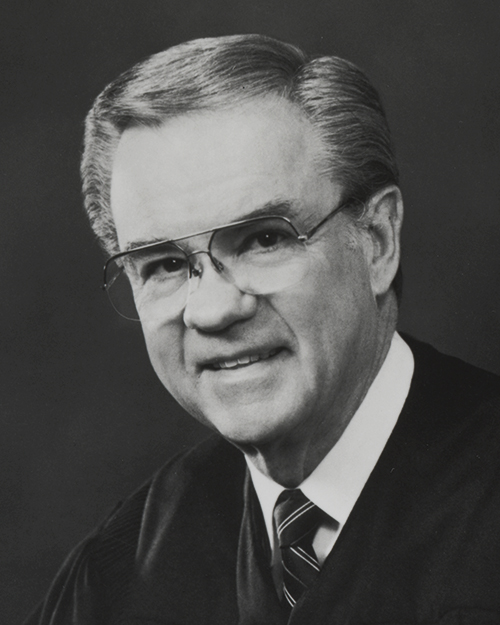

Associate Justice

March 1987–January 1991

In Memoriam

Judge of the Superior Court of Los Angeles County>

Associate Justice, Court of Appeal, Second Appellate District, Division Five (1984 – 1987)

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the State of California (1987 – 1991)

The Supreme Court of California convened in its courtroom in the Ronald Reagan State Office Building, Third Floor, South Tower, 300 South Spring Street, Los Angeles, California, on October 8, 2003, at 9:00 a.m.

Present: Chief Justice Ronald M. George, presiding, and Associate Justices Kennard, Baxter, Werdegar, Chin, Brown and Moreno.

Officers present: Frederick K. Ohlrich, Clerk; and Gail Gray, Deputy Clerk.

MEMORIAM: HONORABLE DAVID N. EAGLESON

October 4, 1924 – May 23, 2003 Justice David N. Eagleson served as the 102d justice on the Supreme Court of California from March 1987 until his retirement in January 1991. Prior to his appointment to the Supreme Court, Justice Eagleson served for three years as an associate justice of the Court of Appeal, Second Appellate District, Division Five from 1984 to 1987, and for 14 years as a judge of the Los Angeles County Superior Court from 1970 to 1984, including a term as presiding judge in 1981-1982. He was president of the California Judges Association from 1979 to 1980. He graduated from the University of Southern California Law School in 1950. Justice Eagleson began his legal career as an attorney in Long Beach, where he practiced general and civil law, both as a senior partner in two firms and as a sole practitioner from 1951 to 1970.

Good morning. We meet today to honor Justice David N. Eagleson, who served with great distinction as an associate justice of this court from March 1987 to January 1991. I would like to begin by introducing the members of the court. To my immediate right is Justice Kennard, and to her right is Justice Werdegar, and then Justice Brown. At my far left is Justice Moreno, then Justice Chin, and then Justice Baxter. On behalf of the court, I wish to welcome Justice Eagleson’s wife, Lillian, his daughters, Beth and Victoria, and other family and friends.

Justice Eagleson joined the Supreme Court after a distinguished career both on the bench and as a member of the bar. He joined this court after almost 2 1/2 years as an associate justice of the Court of Appeal for the Second Appellate District. Before that, he served as a judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court for almost 14 years, where he was an active participant in the court’s administration as well as its courtroom work.

In 1981 and 1982, he served as presiding judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court—a challenging job then and now. He had a history at the court of handling a variety of demanding executive and administrative roles, and during his tenure as presiding judge he was particularly recognized for his efforts at reducing delay in the processing of civil cases. I was a judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court during that time, and I was an admirer of Justice Eagleson’s deep interest in and knowledge of the intricacies of the Los Angeles Superior Court system, and of his efforts to improve the court’s ability to serve the public.

Our career paths also crossed in a different context. Justice Eagleson was president of the California Judges Association from 1979 to 1980. Three years later, I assumed that position. He was a very helpful resource to me in taking on the challenges of that role, and I sought his counsel on many occasions.

Before taking the bench, Justice Eagleson was engaged in the private practice of law in Long Beach, focusing on civil law, particularly probate and business matters. A native of Los Angeles, except for a few years during college and in the armed forces, he remained a California resident throughout his life.

On the Supreme Court, he was known for his straightforward and practical approach to problems—whether they arose from issues in a case or concerns about improving the court’s functions. His legacy at the court includes not only a body of lucid, intelligent, and carefully crafted opinions, but also the lasting mark he made on the court’s internal processes and procedures.

Justice Eagleson was the driving force behind a special court meeting convened to determine how the court would implement a stipulation into which it had entered, agreeing to treat cases as submitted on the date of oral argument rather than on the date the opinion was filed. This new approach required the court to change the way it processed cases in order to comply with the constitutional requirement that decisions be rendered within 90 days after a matter has been submitted.

Under the former practice, years could (and sometimes did) pass between the date of oral argument and the issuance of an opinion, and the public and the parties had no way to anticipate when an opinion might be filed.

The new procedure has provided useful predictability to parties and the public—and is a direct result of Justice Eagleson’s work.

We are fortunate to have someone here today who possesses a far better acquaintance with Justice Eagleson’s work than I have. It is my pleasure to introduce my former colleague and predecessor, retired Chief Justice Malcolm M. Lucas, who shared many a golfing trip, fly-fishing expedition, and legal discussion with Justice Eagleson.

CHIEF JUSTICE LUCAS: An historical era called the Scottish Enlightment occurred in the 1700’s. Famous philosophers came to the fore. One of the greatest Scottish philosophers was Thomas Reid. He became a central figure in a school of philosophy, the philosophy of common sense. Reid and other philosophers argued that all human beings came equipped with an innate rational capacity called common sense, which allowed them to make clear and certain judgments about the world and their dealings with it.

Justice David Eagleson would have been a leading advocate of this philosophy.

He was inquisitive, penetrating, unsentimental, impatient with pious dogmas or cant, relentlessly thorough, rational, but buoyed by a tough-minded sense of humor and a grasp of the practical. He always insisted that decisions be written in clear and straightforward language, avoiding any legal or technical jargon, so that any citizen could read and understand them.

He believed, with Chief Justice John Marshall, this was part of a judge’s responsibility to the principle of self-government, and part of the public’s education in the rule of law, because, as Chief Justice Marshall observed, the entire basis of the rule of law in a democratic society was the “consent of those whose obedience the law requires.” The better ordinary people understood the law, the better for the law, and the better for democracy.

Justice Eagleson had a practical approach to opinion writing. He believed that opinions are written, not for the appellate courts, and not for the author’s pride. They were simply tools to be used by busy lawyers and trial judges. He said a trial judge should be able to pull a volume of the California Reports from the bookshelf and know the holding of a case within 15 seconds. And holdings should be drafted so that they can be quoted in a brief or later opinion in only one or two sentences. As he put it, “too many opinions are like mystery novels.” The authoring judge is confident the reader wants a long, leisurely read of this beautiful opinion and wants to ferret out the holding somewhere in the middle of the opinion. There is food for thought in this view.

I was with him during his entire stay on the Supreme Court. He was a prodigious worker and demanded clarity in his opinions–say what the case stands for, say it up front and give the bench and the lawyers a bright line to follow, if possible. He played it right down the middle. He made life better for me and for his colleagues.

David’s last words to his wife Lillian before his death were: “It’s been a wonderful life. I have done everything I wanted to do.”

And so he had.

He had enjoyed his last years with his beloved and loving partner, Lillian, in happiness and contentment.

As a member of the judiciary he had done everything he wanted to do: a superior court judge, presiding judge of the Los Angeles County Superior Court, president of the California Judges Association, associate justice for the Court of Appeal, Second Appellate District, and then a justice on the California Supreme Court.

All these positions he fulfilled with integrity, dignity, and common sense.

Having done everything he wanted to do didn’t just encompass his professional accomplishments. He had two wonderful daughters and beautiful grandchildren that he loved, and these relationships encompassed many chapters in his book of life.

I know during the course of my life I have met many people, but none more decent and honorable than David Eagleson.

How blessed we have been to have had the privilege of knowing David. We have all benefited from this extraordinary man. He enriched our lives. He lightened our load. He brightened our day.<

He will be long remembered.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Thank you very much, Chief Justice Lucas. It is now my pleasure to introduce Mr. Richard Seitz, a senior staff research attorney at the Supreme Court, who now heads Justice Marvin Baxter’s staff. Rick worked on Justice Eagleson’s staff during the justice’s tenure on the Supreme Court, and we have asked him to share some of his recollections with us.

MR. RICHARD SEITZ: Thank you, Chief Justice George, associate justices, and friends and family of Justice Eagleson. May it please the court:

David Eagleson left an extraordinary legacy in life, in his chosen profession, and in California jurisprudence. Chief Justice George, and Chief Justice Lucas, his great friend, have recounted much about his record of achievement and his capacity for personal affection. To each stage and facet of his distinguished career, he brought the remarkable competence, acuity, loyalty, stability, integrity, and leadership skill that defined and identified him.

I first met Justice Eagleson when he was elevated to this court in 1987, and I worked as his staff attorney until his departure in 1991. Chief Justice George has alluded to Justice Eagleson’s significant influence on the court’s internal procedures. I’ve been asked, from a staff perspective, to share a few thoughts and memories about what he meant to this institution, and to those who so willingly served him here. I do so with pride and pleasure. And I will try to keep it short. When you’ve worked for David Eagleson, you know how important that is.

As all remember, Justice Eagleson arrived at the time of the court’s greatest crisis. In November 1986, the voters had declined to retain three members of the court. Its public image was at an all-time low. Those chosen to fill the vacancies created by the election faced the task of guiding the court through the storm-tossed waters and restoring public confidence in its stature.

Californians can be thankful that Justice Eagleson’s abilities and temperament amply fitted him for the task. His service, and that of his colleagues on the so-called Lucas Court, fulfilled the hope that the court would weather the storm. The role these justices played in preserving the health and stability of the California Supreme Court can’t be exaggerated. David Eagleson deserves his full share of the credit for that vital contribution.

I was a staff attorney for Joseph Grodin, one of the justices defeated in the November 1986 election. The court relies on a cadre of “permanent” or “career” staff lawyers, but in fact, there is no tenure for legal staff. Lawyers may be dismissed at pleasure. This rarely happens, but it was feared, in the toxic atmosphere of the time, that the replacements for the defeated justices would “clean house,” believing they needed new staff with no loyalties to the old regime.

Like his fellow newcomers, Justices Arguelles and Kaufman, Justice Eagleson declined to take that path. Encouraged by Chief Justice Lucas, the new arrivals embraced the long-standing court policy that career staff be retained, if possible, for their legal ability and perspective, and for institutional memory and continuity. Justice Eagleson brought to San Francisco one of his trusted Court of Appeal research attorneys, but he also retained me and every other Supreme Court attorney who wished to stay. We all remained, our loyalty redoubled by his kindness (and good judgment), until his last day at the court in 1991.

His decision to retain staff was consistent with his temperament and philosophy. Though often branded as a no-nonsense conservative, he was, above all, a pragmatist. He distrusted ideology as the enemy of clear and practical thinking. He knew who he was, and he appreciated in others the candor and honesty he himself possessed. As a result, he was comfortable with diversity of views. His Supreme Court staff held wide-ranging legal opinions, which were freely expressed and considered. They could prevail, if persuasive, over his own initial view, but there was never any doubt about who was in charge.

He also believed in order, decency, hard work, and good behavior. This led him to support the institutions, public or private, that promoted and enforced these values. His acceptance of institutional values, and his love of efficient administration, fueled his realization that the court’s permanent legal staff would be a help, not a hindrance, in performing his judicial duties.

Pragmatism, decisiveness, efficiency, candor, fair-mindedness, and institutional respect are also the hallmarks of his opinions for the court. Certainly he was productive. He wrote 54 majority opinions during his four-year tenure, including many time-consuming death penalty cases. All his opinions are marked by clarity of prose and reasoning, and by an instinct for the crux and realities of a legal issue.

Many of these well-reasoned decisions favored the People in criminal matters, and business interests and defendants in civil matters. But he never swerved from his determination to approach each case on its own merits, apply the law to the facts, and let the chips fall where they might. He called them as he saw them, and the results defy simplistic labels.

Thus, in New York Times Co. v. Superior Court (1990) 50 Cal.3d 453 and Delaney v. Superior Court (1990) 50 Cal.3d 785, he confirmed the strong free-press protections contained in California’s newspersons’ shield law. He sided with environmental interests in such cases as Laurel Heights Improvement Assn. v. Regents of University of California (1988) 47 Cal.3d 376, which tightened the requirements for an environmental impact report under California’s Environmental Quality Act, and Western Oil & Gas Assn. v. Monterey Bay Unified Air Pollution Control Dist. (1989) 49 Cal.3d 408, which upheld the authority of the state Air Resources Board to regulate nonvehicular air pollution. In S. G. Borello & Sons, Inc. v. Department of Industrial Relations (1989) 48 Cal.3d 341, he forthrightly concluded that a corporate produce farmer could not avoid workers’ compensation coverage for its seasonal farm workers by requiring them to sign so-called sharefarmer agreements designed to make them independent contractors rather than employees.

His relations with his colleagues were unfailingly courteous and collegial. He would stretch to sign other justices’ opinions if he could do so without violating his own conscience. This policy marked his respect for his fellow justices, and for their views on matters open to reasonable debate. It also highlighted his unsentimental conviction that, in many cases, any rule was better than no rule, and that the court’s ability to speak with one voice whenever possible promoted both efficiency and credibility.

He conveyed these values to his staff. He insisted that our legal analyses be clear, concise, and cognizant of the practical interests at stake. Any new treatise on effective appellate opinion writing was sure to find its way from the judge’s desk to ours. He reminded us time and again that the court’s opinions were not for scholars and academics, but for working lawyers and their clients, who must be able to divine and apply the rules we were announcing.

He had an acerbic wit, which he often kept under gentlemanly wraps. But he could reveal his sense of humor in the service of court collegiality. Once, a staff lawyer—known for his polemic talents—submitted a draft dissent couched in passionate hyperbole. Justice Eagleson read the text, smiled ruefully, handed it back, and said, “I think we’re going to have to edit this with a fire hose!”

Consistent with his lifelong modesty, he always credited his staff for their contributions, while downplaying his own. He was too self-aware to be self-important. He often insisted that he was on the court only because he had been in the right place at the right time, while we were the real legal brains. It was a gross exaggeration, but we appreciated the compliment.<

His adjustment to the court was not entirely smooth. He was not fond of San Francisco’s climate, or its ambience, and he missed his beloved Long Beach. When short-sleeved business shirts and plaid golf pants made their appearance, we knew it was an effort to preserve the trappings and comforts of home.

And when he decided it was time to come home, he did not hesitate. He returned to Southern California and began a new career, applying his exceptional talents to become a respected and sought-after private judge. He continued this work, with great success, until very shortly before his death.

He did not, however, forget the relationships he had forged on the court. Whenever he passed through San Francisco on business, or en route to one of the fishing expeditions he loved so much, he made sure to round up his former staff members for lunch and lively reminiscence. Though the years advanced, he remained unchanged—quick and sharp, in command, and radiant with glowing health. It is almost impossible to believe he is gone.

But our sadness at his passing is tempered by our understanding that he lived a good and satisfying life—in many ways, the best of lives. He was true to himself, he did everything he wanted to do, and he left a record of public service few can match. What more can anyone ask?

Thank you all for gathering today in his memory.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Thank you very much, Rick. I now would like to introduce Ms. Elizabeth Eagleson, one of Justice Eagelson’s daughters, who is a practicing lawyer in San Diego.

MS. ELIZABETH EAGLESON: Thing v. LaCusa, 48 Cal.3d 644. Most legal professionals will remember this as an important case in which this court limited a bystander’s cause of action for negligent infliction of emotional distress. I remember it for an entirely different reason, because when I reached two paragraphs on page 666, where Justice David Eagleson explained that emotional distress is a condition of living that simply has to be borne, I was transported back to the living room of the home in Long Beach, where my sister Vicki and I grew up. I was standing again in front of my dad, perhaps near his lawyer’s briefcase that he always left there when he came home, hearing very similar words about one of my childhood or adolescent catastrophes. And as I envisioned myself in that place again, I thought, “Oh no, no, NO! He is giving his ‘no sniveling’ lecture to the entire state of California!”

“No sniveling” was our dad’s watchword, for himself and for his family. Complaints and fears were invariably greeted with some variation of “no sniveling.” It was hard for us to take sometimes, but we could see that his rigorous application of his philosophy to himself served him well.

“No sniveling” meant discipline. Without the benefit of college-educated role models in his family, Dad lived by the motto “do today’s lessons today. Tomorrow’s will take care of themselves.” Every day presented a new opportunity for accomplishment.

“No sniveling” made Dad decisive. Most of you know he proudly attended USC. What you may not know is how he choose to attend there. Dad had been discharged from the Navy after World War II and was ready to use his GI bill at – UCLA. The enrollment line was long, and by the time his turn came the admissions office was closing. Rather than bemoan a wasted day, Dad recovered his paperwork. He drove across town to USC, where he enrolled on the spot! This, of course, turned out to be a fortunate decision for both.

Dad never complained that others had advantages he didn’t. He figured that hard work would create advantage. His rise from a young lawyer in a sole practice, who typed and served his own papers, to a justice of this court is certainly a testament to the soundness of his belief. Dad’s success was not entirely his own, however. Our mother, Virginia Eagleson, chose Dad when he was a law student with an uncertain future. As equal partners, they built his career. Mom did not live to see Dad serve so proudly on this court. But he knew that her efforts made his service possible.

“No sniveling” also meant frugality. Except for fishing gear and golf equipment, Dad was not a collector. Except for fishing and golf clothes, Dad was not a fashionista. And when it came to interior design, recycled, old, ugly metal office furniture was his choice. Fortunately, our mother had more style. Shortly after they bought their home, the same one where the lectures happened, our mother had upholstered furniture designed for the formal living room, used semi-annually. Nearly 20 years later, in response to changing color trends, Mom wanted to have the furniture recovered. Dad was appalled! Having been sat on no more than three times a year, he could not understand how new upholstery could possibly be needed! Our mother, however, was a tough negotiator, and the furniture was recovered. But, as a condition of the settlement, Dad began to take his morning newspaper onto the off-limits furniture, sitting on a different piece every morning to satisfy himself that the next time she wanted new upholstery there would be a reason to get it!

Dad looked for value everywhere, even from the family dog. Dad wasn’t a fan of pets, believing the inconvenience outweighed any arguable psychic benefits. But one day Vickie came home with a puppy. Believing that a dog should be useful, not merely decorative, Dad decided he would train her to fetch his morning paper. His training method was this: To carry her out to the paper, cradled in his arms like a baby, put her down, and show her the paper. Her response was to immediately trot back to the house, empty-mouthed. This “training” was never successful. But, for many years after that, the dog kept him company while he walked outside to get the paper himself.

By now, I might have led you to believe that Dad was an ascetic curmudgeon. Nothing could be farther from reality. The application of the “no sniveling” philosophy to his life never caused him to skimp on the things he really valued: travel, music, family, friends, his hometown. Although Dad’s work often kept him away from family dinners during the week when we were small, he would come home to sit with our mother, each in an identical rocking chair, one lap for each child, singing to Vicki and me before putting us to bed, then returning to work. He had lifelong friendships because he always made time for them. More recently, he became friends with his five grandchildren, showing them how to fish in Montana and Mexico. And, of course, in his final years he shared all of these interests and attributes with his wife, Lillian. He loved Long Beach and California. For all his travels, he never really wanted to be anywhere else.

When I read Thing v. LaChusa, I recognized not only Dad’s life philosophy, but I heard his voice. I know many of you knew him and will miss him deeply. Sometimes you will wish you could hear his voice again. When you feel like that, do what I will: read those paragraphs in Thing v. LaChusa, listen with your hearts and memories, and you will, like me, hear his voice again. For those of you who never knew him, but want to know what kind of man he was, read Thing v. LaChusa. Dave Eagleson is there and will tell you everything you need to know.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Thank you very much, Ms. Eagleson.

I am pleased to see so many justices of the Second District Court of Appeal in attendance here today, along with the Administrative Director of the Courts and senior members of his staff.

I want to express my appreciation again to all those who contributed their special and memorable remarks to this morning’s memorial session.

In accordance with our custom, it is ordered that the proceedings at this memorial session be spread in full upon the minutes of the Supreme Court and published in the Official Reports of the opinions of this court, and that a copy of these proceedings be sent to Justice Eagleson’s family.

(Derived from Supreme Court minutes and 31Cal.4th.)