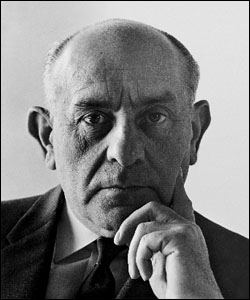

BERNARD E. WITKIN

(1904 – 1995)

The Supreme Court of California convened in the courtroom of the Marathon Plaza Building, 303 Second Street, South Tower, 4th Floor, San Francisco, California, on December 3, 1996, at 9:00 a.m.

Present: Chief Justice Ronald M. George, presiding, and Associate Justices Mosk, Kennard, Baxter, Werdegar, Chin, and Brown. Officers present: Robert F. Wandruff, Clerk; George Rodgers, Walter Grabowski, and Harry Kinney, Bailiffs.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Good morning. We meet today to honor a friend of the California Supreme Court and of the administration of justice and the practice of law in California, Bernard E. Witkin. I would first like to introduce the members of the court. Starting at my far left, Justice Brown, Justice Werdegar, and Justice Kennard. To my immediate right is Justice Mosk and to his right is Justice Baxter and then Justice Chin. On behalf of the court, I wish to welcome Mr. Witkin’s wife, Alba, and other friends.

This is, to our knowledge, the first time that an individual other than a justice or staff member of the Supreme Court of California has been honored with a similar memorial session. The court believed such a tribute was extraordinarily well deserved, given Bernie Witkin’s unique place in the history of the development of California law. Let me take a minute to note here that I struggled a bit over the question about how to refer to the man to whom we pay tribute today. "Mr. Witkin" seemed to befit the solemnity of the occasion, but it was not a form of address often heard by anyone who spent time with Bernard E. Witkin. Instead, he was Bernie to everyone. My use of that name today is a mark of my affection and respect for a man who at his most formal referred to himself throughout his career as B. E. Witkin, member of the San Francisco Bar.

Bernie’s connection to this court dates back to the earliest part of his career. In 1930, he served as a legal secretary, now known as staff attorney, to Justice William Langdon, and to then Associate Justice Phil Gibson. While he was serving at the court, he began expanding his Summary of California law, which even then was an incredible feat.

The speakers today will concentrate on many aspects of Bernie’s career. Nevertheless, I wanted to mention that I am the first Chief Justice and Chair of the Judicial Council since 1969 not to have available the sage advice of Bernie Witkin as an advisory member of the Judicial Council. Chief Justice Phil Gibson was first to appoint Bernie, whose depth of knowledge and unique perspective added immeasurably to the council’s deliberations for over 25 years. I know I speak for the entire judicial council when I say we feel the loss of his guidance.

It is now my pleasure to introduce my colleague, Justice Ming Chin, who will speak on behalf of our court.

JUSTICE CHIN: Mr. Chief Justice George, distinguished Associate Justices of the Court, Justice Epstein, Mrs. Alba Witkin, family, friends, and admirers of Bernard Ernest Witkin.

There is so much to say about this unique and remarkable man. Governor Pete Wilson called him the Guru of California law. Former Chief Justice Lucas said that "[t]he Witkin summaries of California Law made us the envy of the nation." His good friend, Ralph Kleps, said that Bernie was an individual who demanded "conspicuous attention." Certainly everyone will agree that his contributions to California law are unique, powerful, and irreplaceable. He was a teacher, a scholar, an adviser, a mentor, and a good friend to generations of lawyers and judges. He had a special place in his heart for this court and its many distinguished judges and lawyers who were privileged to know him and to work with him. It is for all of these reasons, and so many more, that we gather today to celebrate the extraordinary life of this exceptional man.

For me, Bernie Witkin and California law have always been synonymous. For a young law student, the works of Witkin brought clarity where there was confusion. For a young deputy district attorney, Witkin on crimes and evidence lit the way through the morass of criminal law. For a new civil trial lawyer, Witkin on torts, contracts, real property, and civil procedure were always close at hand to map the way. But I was indeed fortunate that the legal giant behind these great works was also a close personal friend. I was privileged to know the scholar as well as the man. I believe that more than any other single person, except, of course, the Governor, Bernard Witkin is responsible for my appointment to this court.

In many ways, Bernie was like a second father to me. Bernie and my father were alike in so many ways. They were about the same age, grew up during the Depression, came from immigrant families, knew poverty and hard work. They were both very bright, and yet warm and charming. They loved the land and what it could produce, particularly their orchards and gardens. They were great storytellers, and they used the same colorful language. They were both diminutive in size, yet immense in stature. Even though they are both gone, they will continue to influence and to embrace my work and my life.

Only five days before he died, Bernie and I had a long conversation. It was one of those unusually serious conversations. Bernie did all the talking, and I did all the listening. He seemed to anticipate my appointment to the Supreme Court. Of course, he then proceeded to tell me what the court needed. It was only 30 days later that the Governor called with the news of the appointment and to confirm, as usual, that Bernie was right.

But even more important than his influence with the Governor, Bernie tried to teach me over the 30 years of our friendship everything that a good lawyer and a good judge ought to be. For instance, Bernie taught me the Witkin method of legal writing. I can still hear him say, "Write in plain, simple English, without legalese, without arcane Latin, and without footnotes." I’m still working on the footnotes. He also taught me the importance of pure legal analysis and logical organization. But Bernie had many interests outside the law. For instance, Bernie taught me to appreciate fine wine, as well as the musical works of Gilbert and Sullivan. Shortly before Bernie died, my wife Carol and I were guests of Bernie and Alba for an afternoon performance of the Lamplighters, followed by a quiet dinner. Carol and I picked up Bernie and Alba at their beautiful home in the Berkeley hills. Bernie was getting physically a bit frail, so I virtually had to carry him into our van, but it didn’t seem to bother Bernie a bit. He bellowed one of those distinctive Bernie laughs, and we were on our way. The entire afternoon and evening he regaled us with famous Bernie stories. Of course, I had heard them all before, but that didn’t make them less enchanting. It was one of those wonderful evenings where you return home with your stomach aching from laughter. That was the last day I spent with Bernie.

Bernie and I also loved to watch old episodes of Star Trek. One day last December, Carol and I were at home watching Star Trek: The Next Generation. In the middle of the movie, I leaned over and said to Carol, "I wonder if Bernie is watching." Later that evening, we received the message from Alba’s son that Bernie had died.

The next morning I awoke early and went out to get the morning paper. I opened it to read a wonderful tribute to my old friend. When I finished, I looked up. It was one of those cold, clear December days. The sun was just beginning to peek over the horizon. It cast a warm glow of reds and yellows across the morning sky. I said good-bye to Bernie and thought to myself, "Bernie is already up there, making everything better."

As I review Bernie’s life, there is no doubt in my mind he knew at a very tender age that he was destined to influence history. Born in 1904 in Holyoke, Massachusetts, and growing up in San Francisco, Bernie was raised in poverty, and yet he had fond memories of his childhood. From humble beginnings grew a unique and scholarly individual who challenged the legal system and created a whole new paradigm for legal and judicial education.

After graduating from the University of California, Bernie entered Boalt Hall and soon commenced his long career of distinguished legal commentary. Bernie intensely disliked the Socratic method. He thought law professors used it to bully students and to obfuscate the law. Bernie even contemplated another career until he took a bar review course from a practicing attorney. "Instead of concealing the law from us as the law school did," Bernie recalled, "he tried to tell us what it was." Bernie’s belief that bar review materials were, in his own words, "preposterous!" led him to create his own bar review course. He used his carefully crafted and detailed bar review notes as a course outline. This outline eventually became the first Summary of California Law, and with that work Bernie commenced his illustrious career as California’s preeminent legal scholar.

As a young lawyer, Bernie had an unquenchable appetite for hard work, and it was not satisfied with just teaching bar review courses and writing his treatise. In 1930, he became a law clerk to Justice William Langdon. Ten years later, Bernie moved to the staff of Justice Phil Gibson, who later became Chief Justice. The young Bernie learned from the Chief Justice the importance of keeping his personal opinions out of cases, and it was this lesson that helped shape the Witkin we came to know as the objective and brilliant legal scholar. The Chief Justice recognized Bernie’s writing skills and mastery of legal editing. In August of 1941, he assigned Bernie the responsibility of drafting the new rules on appeal.

Bernie completely overhauled California appellate procedure. It was during this period that he began his seven-year tenure as the court’s Reporter of Decisions. The hallmark of Bernie’s years as a law clerk and as the Reporter of Decisions was clarity in writing and succinct legal analysis.

After leaving the court in l949, Bernie channeled his considerable energy into a prolific legal writing career marked by his profound love of the law and his dedication to legal and judicial education. His great promise as a student, as a law clerk, and as the Reporter of Decisions blossomed in splendor in his legal commentaries. His treatises on California law enhanced his recognition as a legal scholar, and in 1982, Bancroft-Whitney established the Witkin Department. Generations of lawyers and judges and even governors were touched by Bernie’s brilliance. But beyond that, Bernie’s simple yet thorough style made the law understandable for all Californians.

Bernie’s love of the law went beyond his legal writing. He started the Foundation for Judicial Education to provide continuing education as well as benchbooks to California judges. He was an advisory member of the California Judicial Council. His contributions to the council continue to influence our legal system and shape the course of judicial education. We are all indebted to Bernie for his willingness to participate in numerous court-related events, including meetings of the California Judges Association, the California Supreme Court Historical Society, and the CJER (California Judicial Education and Research) new judges orientation. The California Judicial College was recently renamed the B. E. Witkin Judicial College.

We are deeply grateful to Bernie’s family, particularly to his dear wife, Alba, for sharing this remarkable man with all of us. Her love, affection, and caring for Bernie made it possible for Bernie to continue to be part of our lives and our profession long after most mere mortals would have passed into the sunset of retirement. Of course, Alba Witkin is an inspiration in her own right. After Bernie’s death, Alba invited me to the announcement of the Witkin Institute’s formation. As she was making her remarks, the woman next to me in the audience leaned over and whispered, "She is so distinguished, she reminds me of Eleanor Roosevelt." But the Witkins not only mirrored the grace and dignity of the Roosevelts; they also shared their commitment to community. In 1982, Bernie and Alba created the Witkin Charitable Trust. Since then, they have donated almost $5 million to over 200 charitable and community groups. They have been benefactors to children, the elderly, and the homeless.

Bernie Witkin was a California treasure. His ideas and his unique body of work will continue to teach, to encourage, and to mold future generations of lawyers and judges in the Witkin tradition of intelligence, simple elegance, steadfast honesty, and good humor. Bernie was a unique and remarkable man. We are sorry to lose him. We shall miss him greatly. We feel honored and blessed to have known him. We know in our hearts that his spirit will never die.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Thank you, Justice Chin. I would now like to introduce the Honorable Norman Epstein, Justice of the Second District Court of Appeal in Los Angeles. Justice Epstein was a good friend of Mr. Witkin’s and for many years collaborated with him in the writing and updating of the second edition of the volumes of California Criminal Law familiar to so many practitioners and jurists.

JUSTICE EPSTEIN: Mr. Chief Justice and Members of the Court:

May it please the Court.

This is a unique occasion, to honor a singular man. Bernie Witkin left us almost a year ago—a few weeks short of the day. He died full of years and full of honors unstintingly bestowed by the people and the system of justice he served for a lifetime.

He served this court, in particular, for decades, beginning well over half a century ago. Alba Witkin, his beloved wife, his guide, and his conscience, will address you about his service here.

I would like to speak of him, for a few moments, in a somewhat broader context.

Bernie Witkin was the Justinian of California. But while Justinian caused the great code that bears his name to be compiled, he did it with the resources of an empire and a cadre of expert scholars who did nothing else. Witkin did it by himself. He started modestly enough, with law school notes that evolved into a grand bar review course. When he began there were typewriters. In terms of automation, that was about it. Electronic aids, let alone computer technology, were beyond Buck Rogers. In fact, he began before anyone had heard of Buck Rogers.

He took it upon himself to write nothing less than a Summary of California Law: contracts, torts, real property, equity, constitutional law, tax, agency and partnership, negotiable instruments, and more. Imagine the hubris in undertaking a task so large at an age so young. Only a law professor would even think about doing it at any age. Bernie knew a large number of academics, and was a close friend of many of the best. But he never aspired to, and never held, the title of professor.

The Summary was a success. It was followed by series on procedure, evidence and criminal law. Each was successful, and each was followed by new editions as the supplements outgrew their parents.

Bernie’s works became so well established because almost all practicing attorneys, and almost all judges, used, cited, relied upon, and used them again. What made them so special? After all, there were such things as legal encyclopedias, and specialized works on all sorts of subjects. And there was that masterful work, the Restatement of the Law, that is nationally authoritative in so many areas.

Some works attempt to capture too much and end up saying more than can be absorbed about a subject. They drown it in words and citations. Witkin’s work is different. It presents a clear statement of the law. As one of the legal portraits of Bernie put it, he "lays down the law." But he does it with supporting rationale, and in context. When you read what he has to say about a subject, you know the "what" as well as the "why." And you see, presented tersely but fully, the development of the area. You see it in context with related subjects. What you do not see is a superfluity of detail. There is no underbrush of words; no legalese. One would look in vain for the usual "hereinbefores" and other amalgamated words, or for Latin terms that have not worked their way into the language. There is wit, but no witticisms. And no footnotes. None.

The Witkin texts occasionally question precedent—usually an elderly precedent ripe for review. They do not "predict the law," although they cite law review and other periodical comments that try to do so. It is enough to state and keep up with the enormous volume of law as provided by those who make it by enactment and through judicial construction.

In a society governed by law, what greater contribution could there be? Witkin’s great gift is that he enabled lawyers and judges—generation after generation—to know and understand the law, and to apply it in all its vastness, its intricacy, and its majesty. It is not too much to say—indeed, it is not enough to say—that the profession, the bench, and the society they serve are better for it.

Bernie was a paradox. His aversion to traditional Socratic teaching is well known; it almost did him in during his own law school career. Yet he became one of the greatest and most quoted legal scholars of his age. He never used a computer or any of the newfangled devices that most of us can no longer live without. But he was a futurist, with a clear vision of the demands that would be placed on the legal and judicial systems in the years ahead. He demonstrated that vision during his decades of service as an adjunct member of the Judicial Council, the CJER (California Judicial Education and Research) governing committee and, more recently, as a member of the 2020 commission. He could have had more degrees than a thermometer, yet the only title he ever used—and it appears in all his books—is "B. E. Witkin of the San Francisco Bar." For a great deal of his life he worked without a staff. But he came to recognize mortality and trained a superb body of lawyers at Bancroft-Whitney to write (as he said) as well as he. He did not serve as a member of any court, yet he is honored today by this great court.

I was particularly privileged to work with him and to know him well during the 16 years that I co-authored one of the Witkin treatises. It was the richest experience I have had.

Bernie was easy to talk to, as thousands of lawyers and judges came to know. He could put over a story as no one else could do. His robust humor, which included balancing objects on his head while being otherwise nonchalant, and that patentable two-note laugh, are well known. To many, so is the hospitality of Bernie and Alba. And, more recently, so is their generosity. The generosity is not new; it is just that neither Bernie nor Alba sought recognition for the gifts and grants they bestowed—for legal education, for the arts, and in so many other areas.

He virtually created formal judicial education. What is now acknowledged as the finest, most comprehensive judicial education program in the nation was founded by him and a handful of others. It was endowed by him, and firmly supported by him for the rest of his life. It remains one of his monuments.

There will not be monuments in the sense of statues and the like. Some legal institutions will bear his name (as the Judicial College does now). But his monument is in this chamber and wherever a California court sits. It is all around us. And it will endure.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Thank you Justice Epstein. Next, it is my great pleasure to introduce Mrs. Alba Witkin, Bernie’s wife. Throughout their marriage, Mrs. Witkin served as an essential component, not only in supporting her husband in his work and appearing with him at events up and down the state of California, but also—as noted by Justice Epstein—in managing the Witkin Charitable Trust, an extraordinary fund that has quietly and effectively contributed to a wide range of legal and other causes.

MRS. WITKIN: Good morning. Thank you for honoring Bernie in this very singular fashion. In his wildest dreams, I don’t think Bernie would have imagined that the Supreme Court would have done this for him. But he would have liked it, and in his immodest humility, I think he might even have thought he deserved it. I know that it is in part because of his contributions to the legal community, but more so, because of his years of service to the Supreme Court that you are honoring him. And I am very grateful to you for that.

For 65 years, he knew each and every Supreme Court member. The media used to ask him about the Supreme Court members, and so, after a time, he did the "state of the union" address about the Supreme Court. He would give this speech to various legal groups, and they were always glad to hear his humorous and witty interpretations.

Over the years after he left Supreme Court employment, he continued, as you know, his relationship, his very serious relationship, to the Supreme Court through the Judicial Council, as an advisory member. He was very happy to do this because he was always very concerned with everything that had to do with the legal system.

I think one of the most important roles that he served was when he gave his historical perspective to all of the things that he was asked about. He would sit quietly, I know, at most committee and Judicial Council meetings, but when asked, he could explain a great deal. His incisive mind, his memory, which was prodigious, could always produce a total review of everything. But most important, it was as this elder statesman that he served an important role. He could, when asked about any particular event or any particular case, speak about every detail, every fact. And so it was this total view that he was able to give. Where he might not remember what he had eaten the night before for dinner, he could recall in detail things that had happened 30, 40, and 50 years ago.

I know that you all have been told that he was outstanding in another regard—that is, as the father of judicial education in starting CJER (the Center for Judicial Education and Research). He was on its governing board for years until his death. He spoke at every summer college and, of course, now the college is named after him, and I think very aptly so.

He also spoke to every judicial orientation class that came, the class of new judges, except if he were out someplace else in California or in the nation speaking.

You have heard from Justice Chin a very thorough and beautiful report of his life, and you have heard from Justice Epstein about the particulars of his legal writing and his legal career and his professional life. I thank you very much for what you have done for his memory today. And I thank you also for the warm friendship that you have extended to me because of your love for Bernie. Thank you very much.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Thank you for those warm words, Mrs. Witkin. I want to thank again all those who have contributed their eloquent remarks to today’s proceedings.

In accordance with our custom, it is ordered that this memorial be spread in full upon the minutes of the Supreme Court and published in the Official Reports of the opinions of this court, and that a copy of these proceedings be sent to Mrs. Witkin. In addition, it is ordered that the transcript of the memorial proceeding held in honor of Bernard E. Witkin in Berkeley, California, on January 13, 1996, also be spread in full upon the minutes of the court and published as an addendum to these proceedings in the Official Reports.

PART II

"The law is the true embodiment of everything that’s excellent. It has no kind of fault or flaw, and you, M’Lord, Embody the Law."

Gilbert and Sullivan, Iolanthe, Act I

Zellerbach Hall, Berkeley, California January 13, 1996

JUSTICE NORMAN L. EPSTEIN: Thank you. Good afternoon. I’m Norm Epstein. You and I are here as friends of Bernie Witkin, to remember the man, what he was, what he stood for, and his legacy. This is not a service. It is a celebration of an extraordinary life.

There was a cover article about Bernie published in the Los Angeles Lawyer some 11 years ago. Perhaps you saw it. If you did, you were probably struck by the full-page picture of Bernie, caught by the camera in a portrait that was typical even if posed. There he was, working at his manual, very vintage Royal typewriter with a stack of print manuscript, a pile of cardboard ends of legal tablets taped together, scissors, and a paste pot. That’s how he worked. He was dressed in a pullover and wore glasses and that impish smile as though he had just told you something very funny that had a special meaning known only to him. You might see that smile by looking at the wonderful drawing by Terry Flanigan, which is on the program. Bernie was surrounded in the picture by the law books from which he drew so much substance and some disdain. Nearby was his lovely and supportive wife Alba, who infused so much love and common sense into Bernie’s life. And outside was the orchard and the vegetable garden and the plantings on which he lavished so much attention. He labored on them part of each day that he was home, weather permitting. He loved to make things grow and flourish. And in a general way, doing that was his life. And finally, Bernie was surrounded by this entire overlitigated, vibrant state to which he contributed so much and which gave him in return its unstinted adulation. It did so because he was unique. A scholar whose own law school experience was, well, unfulfilling. A man who, more than any other in contemporary jurisprudence, has mastered and understood the law. All of the law.

If, instead of looking at Bernie at work in his study surrounded by concentric and increasingly comprehensive settings, we could travel back through the many decades that held his career, we would see him developing the treatises that together substantially reflect the entire body of California law. And we would see him at the beginning of organized legal education in this state and, in particular, the development of judicial education, for which he was very much responsible. Back to the years of the prewar and postwar courts of Chief Justice Gibson and the reorganization of the state trial court structure and of the Judicial Council. And there is Witkin. Drafter of the rules of the Judicial Council. Reporter of Decisions. Law clerk to two Supreme Court justices, including Chief Justice Gibson. And we would see him finally as a student and classical debater, from which experience he learned the virtue of organization, the principle of selectivity, and the habits of clarity, succinctness, wit, and accuracy that characterized his entire professional life.

The distinguished persons who will address us this afternoon remember Bernie from different but somewhat overlapping perspectives. Bernie would revel in knowing that so distinguished a group has assembled here on the stage and in the audience. Although Bernie was not a judge, he was very much involved with judges and the administration of justice. He was an honorary member of the California Judges Association (the only one) and he served for decades as an advisory member of the Judicial Council. He was a friend of generations of members of the Supreme Court. One of those members whom Bernie especially respected passed away just two days ago, Otto Kaus.

Beloved by those who knew him and held in the highest esteem by all who read and used his work, Bernie also was a strong supporter, an admirer, and a sustained friend of the Chief Justice. The Chief Justice is the first of the distinguished persons who are going to address us this afternoon. It’s my privilege to introduce him now. Ladies and gentlemen, the Chief Justice of California, Malcolm M. Lucas.

CHIEF JUSTICE MALCOLM M. LUCAS: Thank you ladies and gentlemen. And parenthetically thank you for the beautiful music that we all have been enjoying. As I prepared for this memorial, I couldn’t help but think about Bernie’s ability to summarize and to synthesize. He could make the most complex legal concepts easily understandable. Bernie’s life and his contributions to the law are so extraordinary that it would take someone with his special skills to really do them justice. I can’t claim those talents, but I can claim to speak from deep affection and respect for a remarkable person.

It is not unusual these days to encounter a measure of cynicism about the law and the administration of justice. Too often the practice of law seems to be viewed more as a business than a professional endeavor. To Bernie Witkin, however, the pursuit of the law and the administration of justice never grew stale or dull. He remained perpetually engaged and passionate about the law and about our system of justice. He truly loved the law. To him it was not a harsh mistress. It was instead an eternally inviting companion offering ever-changing delights.

Bernie vastly improved the quality of the practice of law through his work. Having access to Witkin on California law makes our state’s lawyers and judges the envy of every other jurisdiction. I’ve been a judge at the superior court, the United States District Court, and the California Supreme Court level. I therefore speak with some experience when I say just how significant his work has been to the development of the law in our state. Just last Wednesday during oral argument two counsel in a particular case both cited Witkin as holding the key to the case, which is always interesting.

As Chair of the Judicial Council I was privileged and happy to continue a long tradition of appointing Bernie as a special advisory member. As a matter of fact, I appointed Bernie to everything that he could and would do for me. He was a member of the California Supreme Court Historical Society, and of course made great contributions to that. He was a member of the various committees that did important policy making. And we would meet either personally or by conference call regularly. He always made excellent contributions to anything that he was involved in. Besides having the Witkin wit. And he was a faithful participant in all of that. And as I said, with just a few comments emerging out of a wealth of his experience, he invariably put the problems and concerns of today into broad and helpful perspective.

Bernie shed light on the past for us in two irreplaceable ways. First, by his legal treatises. And second, through sharing his wealth of experience and knowledge about the administration of justice. But he also challenged us to look ahead. He served as a model by remaining open and receptive about change and growth. Bernie never feared what lay ahead. He embraced it. Beyond the books and the legend was a warm and caring man. Bernie cared a great deal about the education of judges. But he did more than create and maintain the finest judicial educational system in the nation. He also appeared at every new judge orientation to put his personal mark on the importance of continuing education. And occasionally he would put his personal beer bottle on his head and balance it for those of you who have been to those sessions, while talking volubly with you. I always refused to comment on it because I didn’t want to give him the satisfaction of showing that I was startled by him doing this. His philanthropic contributions were made quietly. He and Alba, his wonderful wife, partner, and constant supporter acted without fanfare to directly benefit the many causes that they cared about.

Bernie cared about the law and he cared about people. He had a mind of great brilliance and a heart of great depth. And he had a laugh that lived up to both. And an endless supply of jokes to keep him and the rest of us laughing. The last time I saw Bernie was at the California Supreme Court holiday or Christmas party, just a few days before his passing. He was in good spirits and he spoke to us. He regaled us with some carefully selected stories as only Bernie could. His last offering had a punch line that was a play on the song title "Some Enchanted Evening." As he returned to our table the pianist began to play the song. I leaned over to tell Bernie that every evening with him was enchanted. His unpatentable laugh echoes in my ears now as I think of that moment. Thank you, Bernie, for your friendship, your wisdom, and all the enchantment you have spun for us over the years. I will miss you.

JUSTICE NORMAN L. EPSTEIN: Thank you, Chief Justice. Bernie was not a judge. He was not a professor either, and he was almost never—at least in my hearing—referred to as Mr. Witkin. It was just Bernie. In all his books the only appellation that he used was B.E. Witkin of the San Francisco Bar. Although not a professor, he was a longtime and ardent supporter of legal education, in law school and ever after. And he especially supported his alma mater, Boalt Hall. Its dean has been a friend of Bernie and Alba’s for many years. I’m pleased to introduce her to you now. She is our next speaker, Dean Herma Hill Kay.

DEAN HERMA HILL KAY: I am honored to represent Bernie Witkin’s alma mater, Boalt Hall, and to join his family and friends here today to celebrate his life and to bid him farewell. Bernard graduated from Boalt in 1928. He became one of our most distinguished and most beloved graduates. I like to think that Bernie loved his school as well, but it is no secret that he did not love law school while he was a student. In fact, he frequently remarked that he detested law school for its time-honored Socratic method of teaching, which he claimed dishonored Socrates and insulted students, and for its impracticality. He freely confessed with a twinkle in his eye that he cut as many classes as he could manage. Whenever the opportunity offered, at alumni gatherings, student events, or law school dinners, Bernie told a succession of Boalt Hall deans exactly what he thought was wrong with legal education. He was never shy about offering his advice, and he told it as he saw it. "If you want to train lawyers," he would say, "don’t forget to teach them how to practice their profession." He never balanced a beer bottle, Mr. Chief Justice, at the Boalt events. Maybe that’s because we didn’t serve beer—but he did balance salad plates to the great amusement of everybody in the room.

In his own work, Bernard practiced what he professed. His path-breaking Summary of California Law, now in its ninth edition, is a masterpiece of clear and concise legal analysis. He devoted his life to teaching the law to lawyers and in the process he almost single-handedly raised the intellectual standards of the California Bar and judiciary until the legal profession in this state has become an example to the nation. He has been honored many times and in many different places for that superb achievement. And justly so. His legacy is immense.

Recently, Bernard Witkin’s law school proved itself ready to take some of his advice about restructuring its clinical program. And Bernard was characteristically ready to help. He and Alba Witkin generously supported the new directions we are undertaking. When their gift was announced Bernard was quoted as saying, "The clinical education program at Boalt can be the triggering event for the establishment of practice education in law schools throughout the country." Indeed, I hope that when it is established, Boalt’s new program will live up to Bernie’s hopes.

All of us at Boalt are proud of Bernard Witkin. Proud of his high ideals for the profession. Proud of his own example of excellence and legal research and writing. Proud of his passionate love of the law and his knowledge of how the power of law can transform society. Beyond our pride however, is our affection and our love for Bernard and Alba Witkin. They have been an inseparable part of the life of the law school for many years. So in the name of Boalt Hall, I thank Bernie. I say farewell to him and I hope that Alba will remain close to us in the years to come.

JUSTICE NORMAN L. EPSTEIN: Thank you, Dean Kay. In just a moment we’re going to hear another distinguished graduate of the Boalt Hall School of Law. We are honored that the Governor and Mrs. Wilson are both here to honor Bernie’s memory. I know, Governor, how much Bernie appreciated the warm remarks and public comments that you have made about him, particularly on the occasion of his being honored at the Sacramento Bench and Bar media dinner a couple of years ago. And especially for your confirming him in his title as Guru of California Law. I’m reliably informed that no other state has or has had its own Bernie Witkin—a single individual whose authoritative writing encompasses virtually the whole of jurisprudence in the state. He was the special treasure of California. Here to speak for the people of California is its distinguished Governor. It is my distinct privilege to present him. Ladies and gentlemen, the Governor of California, Pete Wilson.

GOVERNOR PETE WILSON: Thank you very much, Norman. Thank you ladies and gentlemen. I am here really in two capacities. First, as Norman has indicated, I am honored to be here in a representative capacity as the Governor of California to try to express the enormous pride and gratitude that we all feel for the remarkable, unique contribution which Bernie Witkin made to his state in interpreting its law. Second, I’m here in a representative capacity, representing all of those desperate, terrified law student refugees from the Socratic method who so frequently (and often under great duress) resorted on the eve of examinations to Witkin’s Summary of the Law. It was blessed relief.

As a first year student, I also had a job in the law library. I used to dread Sunday nights when Dean Prosser would come into the library with his gold pencil clenched in his teeth like a pirate with a dagger. He would lay waste to the library. In 20 minutes he would cause me at least an hour and a half’s work in terms of reshelving the case books. If you knew Dean Prosser, you knew that he was not a man who suffered fools gladly. He was not necessarily generous with praise of other scholars. On the loan desk with me one of those evenings was a brash first year student who, evidently feeling that he had no need to fear for his graduation, said one night to Dean Prosser, "Dean, don’t you think that Witkin is really superb?" I waited with bated breath, and the great man turned and snarled, "He’s damn good." From Bill Prosser, that was uniquely high praise.

It is praise that was long since earned. A friend of mine, a lawyer in another state, said, "I keep hearing about Witkin and finally I saw some of his writing the other day. Extraordinary. He really dominated California law, didn’t he?" I said, "There are lawyers who haven’t read a case in years but they read Witkin."

And of course, there were law students who, after the first year, didn’t read many cases but who were desperate to read Witkin. And, as you have heard, Bernie believed that the best judges were strict constructionists, who left the making of the law to the Legislature. Even more fervently he believed that the teaching of the law was much too important to leave to law schools. And, in fact, he made it his business—as you have heard—to teach lawyers, to teach judges. And he had an extraordinary impact.

Now it is also well known that among his many virtues, humility was not foremost. It is said that Sir Winston Churchill once described the late Clement Attlee as a wonderfully modest man, but then he added, he had so much to be modest about. I think the converse was clearly true in the case of Bernie Witkin. He was endowed with an immodest talent and with an inordinately gifted ability to make the complex clear and succinct. You’ve heard that from Norman. You’ve heard it from the Chief Justice. And to all of us who have read with relief his explanation of some complexity in the law that was abundantly clear.

And if I stop to think about it, the impact that he has had upon our lives is extraordinary, not just on the lawyers but because of the impact of the law upon the lives of all citizens. If you have bought a house, if you’ve taken a second mortgage, if someone needed to explain to you the difference between a deed of trust and a mortgage in another state, if you were arranging to enter into a contract or a prenuptial agreement, if you were trying to leave something to your children through an inter vivos trust, then you have been affected by Bernie Witkin, because he affected the lawyer who was trying to effect this for you.

And the extraordinarily thing, of course, is that he managed to do all of this with great good humor. The law didn’t have to be the ponderous thing that so many of us thought it must be in the first year. He punctuated life as well as his teaching of the law with as much fun as he could find. And the result was that he was much in demand. As a teacher he could make anything seem clear, even the rule against perpetuities. If I ever knew what the hell that meant, I’ve long since forgotten—most people think it is simply a prophylactic against bad political speeches. But Bernie had the special gift of making the law live, making it interesting, even making it fun. I’m told that at about the time he chose a legal career, he had been tempted to become a professor of speech at a university in a neighboring state. Happily for us, he declined that honor, and instead chose Boalt and a legal career. We thank the Lord because, as they so often say, the rest is history.

No one will ever again be so prolific. It’s difficult for me to conceive of anyone reading all that Bernie has written, much less that one man actually wrote it. It is difficult for me to conceive of someone who will have nearly the far-reaching impact that he and Alba will have through their generosity and their philanthropy. I think perhaps what we ought to remember (and Herma and Malcolm and Norman have spoken to it, as will those who follow me): he was a very good guide. Not just to the law but to life. And he always seemed to manage to find time for the other things and put into perspective the work that was his consuming passion. And he had a very practical side that made his work immensely important. But in addition to the work there was wine. And of course, there was Alba.

Most of us can hope to be remembered, hopefully with some affection, by a few friends and those whom we love. Bernie for all of his diminutive stature will continue to cast an enormous shadow because he was in fact unique. Not just a great scholar. Not just a superb writer. Not just a truly great teacher. But someone whose practical enthusiasm for the law was translated into the improvement of the bar and the bench. So when we think of Bernie Witkin in years to come it will be with a number of personal anecdotes in mind that give great pleasure, but for those who were denied the pleasure of his company, they will be enriched for decades to come by a legacy that is extraordinary because he left behind better lawyers, better judges, better law and, I am convinced as a result, a better society. That’s quite a legacy. I think most people who knew Bernie not only treasured his company, but envied him. And he was to be envied. He was an extraordinary human being. He will live on and on, I think, for decades. The State Bar named for him the prize it gives annually to the individual who has made the greatest original contribution to the improvement of the law. It was simply an acknowledgement. It should be bearing his name and will appropriately, but it will be very difficult, even for the distinguished recipients of that prize, to live up to the legacy left by the first recipient.

JUSTICE NORMAN L. EPSTEIN: Thank you, Governor. The next speaker is my own leader. Mildred Lillie is the Administrative Presiding Justice of the Second Appellate District. Justice Lillie has been a long-term admirer and friend of Bernie. There is no Court of Appeal judge in California who has earned or who has received greater respect from her colleagues and from the bar than she. Ladies and gentlemen, Justice Mildred L. Lillie.

JUSTICE MILDRED L. LILLIE: Ladies and gentlemen, and thank you very much, Norman. Bernie Witkin was a vigorous advocate of judicial education and he was a born teacher. For close to 70 years he taught the legal profession through his seminars, courses, and lectures, which he delivered with great flare, humor, and insight, and his writings, in which he simply told us just what the law was and how to apply it. He started teaching early, beginning with a bar review course which had its genesis in his law school notes. He never tired of reminding me, preferably when he had an audience, that I am one of his oldest living law students. So what can I say? It’s true. In 1938, after graduating from Boalt Hall, I took Witkin’s bar review course in San Francisco, which Bernie himself taught. And for 58 years thereafter, through his lectures and writings, he brought a continuity of legal learning into my professional life.

My journey through the court system began about the time Bernie’s treatises were evolving into what for years has been every lawyer’s and judge’s bible. Through him we got to know the whole of the California law without wading through tomes of extraneous material. Succinctly defined and cut-to-the-core principles of law and their use, the newest changes in the law, the most recent authorities, and the policy behind the law were given to us in terms of common understanding. He had a great gift for analyzing and explaining the law and an even greater gift of clarity of expression. He has guided us in the throes of indecision and just plain ignorance.

Now on a personal plane, he enriched my life with his personal friendship and his counsel, advice, and encouragement, given through the years with great generosity of heart and spirit. But there is something else. Something steadfast in my memory and in my heart. In the last portion of the last decade, Bernie Witkin taught me how to treat the advancing years and to enjoy them with humor and with equanimity.

Bernie Witkin did not just belong to Alba or to Bancroft-Whitney or to Norman Epstein or to you or to me. He belonged to everybody in the legal profession. He was a generous, gracious friend and a very special human being. His brilliant mind and ebullient spirit are stilled. But Bernie Witkin left a legacy that will continue to enrich our professional lives. Alba, there is much to cherish. My husband and I wish you comfort, serenity, and peace in your devotion to Bernie’s memory.

JUSTICE NORMAN L. EPSTEIN: Thank you, Justice Lillie. A. Alan Post is known to us as California’s second and longest serving Legislative Analyst. He has continued to serve California on a number of special commissions, and he stands for—in fact, he personifies—good government. But more pertinent to us now, he and his wife Helen are among that small band who were present at the creation, the people who brought Bernie and Alba together. It is my pleasure to introduce Mr. A. Alan Post.

A. ALAN POST: Ladies and gentlemen, I have learned a lot about the law today from those who are lawyers, and you should understand that Alba Witkin and I are the two speakers who are not lawyers. So I want to speak to you today about Bernie as a friend. My family have known Bernie for about 35 years. We were bonded to him by the fact that he married two women that we knew before Bernie married them. Janie and Alba. We have had many, many days and evenings and extended visits with the Witkins over the years. We also were very close to three of Bernie’s mutual friends, the former Chief Justice, Don Wright, and Ralph and Patricia Kleps. Ralph, as a matter of fact, first introduced us to Bernie. We were always amazed by Bernie’s vigor and his humor, and, as has been mentioned here today, his idiosyncracies, his eccentricities. Those that have been described to you today took place in his home as well as in the public scene. Bernie was not given to conspicuous consumption, although he lived well. He had a beautiful home. His garden, which has been mentioned. Beautiful wine cellar. Tennis court. Swimming pool. Lovely things to live with, and Bernie loved his home.

What really drove Bernie, however, was his desire to play the game of conspicuous attention. And he was a good listener, but in a social setting not for long. Bernie would say, "I’ve an announcement to make." And then he would make some announcement, generally very funny. Or he would say, "Nobody," he would complain, "nobody’s listening to me." And he would get into the stream of conversation again. Or, as has been described to you already, that final attention-grabbing act. He would place a wine glass full of red wine on a blonde carpet and prance around the living room with it on his head and naturally everyone was frozen, waiting to see what was going to happen. I’ll never forget Bernie at our son’s wedding, shocking the people who didn’t know him by seeing this diminutive, serious man walking about through all the rooms with a glass of red wine on his head.

We came to expect Bernie’s stories. Bernie had an extraordinary, really unbelievable articulation. He could frame words in a way that I’ve never heard anyone else do. And he was extraordinarily intelligent. And he also had the dramatic ability to exploit all of these talents. And he did, regularly. The Witkin wit has been mentioned. Bernie told his stories over and over again. And we knew they were coming. We knew what they were, but he told them so beautifully, so exquisitely that you just loved to hear them over and over again. We celebrated New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day for years with the Witkins and we got the same stories for maybe 15 years in a row, but although the cast of characters in the audience changed, we all had heard them many times and we really appreciated them.

But the Witkin wit was unexpected. You never knew quite what was coming. In our house, we’ve been collecting art for about half a century. Sculpture, painting, art from all parts of the world. The house is crammed with it. And most people when they walk in the house say, "Ha, this looks like a museum." Well, one day when Alba and Bernie were going out of the house, Bernie, with that sort of Jack Benny pause of his, turned around and surveyed the assembled guests and said, "What a garage sale this would make."

Alba brought affection and companionship to Bernie, as did Janie. But she also brought a much heightened awareness of public policy issues and social consciousness that was latent in Bernie. It was always there, but I think because of Alba’s lifelong involvement in public affairs and social causes, it was reawakened in a way that was extraordinarily fruitful in the last more than a decade of Bernie’s life. And she played a very strong role in framing his final years.

Bernie was a beloved friend. He was a kind man. A generous man. He was loyal. Ever entertaining, ever interesting. He was truly unique. We sort of calculated that he would outlive all of us. And I’m sure, in his works, he surely will. Thank you.

JUSTICE NORMAN L. EPSTEIN: Thank you, Mr. Post. Phil Isenberg also stands for good government. He has been Mayor of Sacramento and represents that constituency in the Assembly where he has been Chair of the Judiciary Committee. He has been a good friend of Bernie and Alba during all of his considerable service in the California State Legislature. I’m pleased to present him now, Assemblyman Phil Isenberg.

ASSEMBLYMAN PHIL ISENBERG: Seventeen years ago I received a call from Alba Cushman. Alba was a young woman of prominence in Sacramento, formerly on our school board, and a woman about whom one always said when she came into the room you rose to your feet no matter who you were or what you were doing. I was the mayor then, and Alba said, "Phil, would you and Marilyn please join us for a private, confidential dinner in old Sacramento? And I’d appreciate it if you would not mention that you’re going to a dinner like this." An odd kind of telephone call, all things considered. And I could not resist and I said, "Well, Alba, what is this about?" Politicians are leery of dinners where you don’t know what you’re doing. And she said, "I’m getting married." Well, this was pretty serious news, all things considered, and I said, "Alba, to whom?" And she said, "Bernie Witkin." "Alba you can’t marry Bernie Witkin. He’s a book!" Which is true. As Norm indicated, we’re kind of doing this chronologically through Bernie’s long life and I’m (I don’t look it) the youth brigade of this activity. But for those of us who practice law and knew Bernie Witkin as a book, it was truly shocking to know that behind that binder was this diminutive elf of a man who was absolutely able at all times to dominate every conversation. Not even the Chief Justice could stop him in the midst of his speech, although the Chief did try at times, looking grim as Chiefs are wont to do, and looking sternly at Bernie. Bernie would pay no attention to him at all and would keep going.

We went to dinner that night and met Bernie for the first time, and were exposed to the full range—though not the glass of wine on the head—the full range of Witkin. And we were also exposed to Alba’s induction to the "Now Bernie" club, which I presume is a club of friends who will say to Bernie Witkin when he says one of his outrageous things, "Now Bernie," hoping that that would deter him, put him on a different track. It never did.

Now for those of you fortunate enough to have known him, to have worked with him, to have talked with him, to have socialized with him, he had a number of characteristics. God, he could talk. Oh, he could talk. I was over at Bernie and Alba’s house earlier this week and one of the guests there said, "Oh, Bernie will be at the memorial service today." Well, if he is here, he is on better behavior than ever before in his life. Ordinarily in a Witkin event, there was only one speaker and none of us would qualify. There’s a sign over the door to his offices at home. I don’t know how many of you have seen it but it was one sign of Bernie. It says, "You are entitled to the benefit of my thoughts." On the reverse side of the door as you leave the office are two huge carved wooden quotations. The first is by Dr. Samuel Johnson. It says, "No man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money." Not a bad admonition. And then below that a quotation by Confucius Junior, one of the nom de plumes that Bernie used throughout his life for his made-up quotations. It says, "No man but a blockhead ever wrote only for money." And I suppose that in fact says a lot about Bernie Witkin. Also Alba made me promise not to mention numerous other signs and plaques in his office that say other things.

He could talk and he could write and he could think, and that’s what he did his entire life. He died at age 91, which is staggering when you think about it. In the last year of his life, Alba said, he did slow down a bit. He only gave 50 speeches. Only gave 50 speeches. For a man so insistent that his works and his professional efforts be accessible and readable to lawyers and judges. I mean he insisted on writing his books in simple English as opposed to, God save us, the legalese in which most of us engage. He insisted on making bench books available to the bench. He insisted early on in using computer disks and putting the information on them. He insisted on using CD-ROM’s, new technology. But for all of that, as Norm indicated, he operated in this funky office at home, that many of you I know have seen. So imagine 450 or 500 square feet, floor to ceiling court decisions, some of the binders are a little ripped and Bernie’s name stamped on there, Supreme Court, Court of Appeal. I didn’t see any Deering’s Codes anywhere, Bancroft-Whitney. I don’t know where he did keep the Deering’s. One of his perennial complaints was to criticize his own book publisher for what he considered the failings of their publishing efforts. He had a big battered desk sitting there, a wooden desk. He had his beat-up Royal manual typewriter that he was still typing on. He had, as Norm indicated, those terribly long pointy scissors that he used. You know, the kind that parents immediately hide on the top shelf, if you have any children. And he had these huge pots of glue, of paste. And the brand he was most fond of apparently from the pots of glue around his office was called "Kid’s Paste." Big label "Kid’s Paste," you know, with the little brush in the top. I mean, looking at those bottles is kind of like looking at your childhood in the face. But it all says something else about Bernie. There was something remarkably charming and fresh and engaging and youthful about him, right to the end. Alba said that room’s almost clean now. I find that hard to believe but it is conceivable that more might have been stuffed in that room than was there recently.

But I do know a couple of other things. His speeches, and he gave thousands of them over the years, were always works in progress. He took his old speeches and he reinvented and revised and he’d cut and paste. That’s what he’d use those things for. It’s an historian’s nightmare, because his speech of 1993 would be composed of snippets taken from his speeches of 1951, 1967, 1962 all jammed together, no doubt destroying the previous speeches in the process. And then adding his new and contemporary and current thoughts as he went along.

The second thing about Bernie is that he always looked ahead. This was a man not lost in the past. He loved to reminisce but he was not lost in the past. There are boxes everywhere in his house and in his office. Alba said he would not let her file anything. So he had this idiosyncratic filing method. He used envelope boxes and stationery boxes, not exclusively but predominantly. I counted 81 of those in his office there, and they were all labeled with different things. But there was one that impressed me more than anything else. It’s labeled as follows: "New material on various substantive subjects for 1996." Ninety-one years old and he’s working for 1996. I do not know many people who are able to do that. And let me just tell you what that little box contained. It contained his first revisions to last year’s Witkin’s Procedure book for 1996. Appropriately starting with the courts and with judicial discipline as subjects. It included 200 pages of torn-out court decisions cited and noted for reference and inclusion in his new volume. It included 50, 60, maybe 70 law review articles that he thought were interesting that I would think I was doing pretty well to read, that he had read and added and the range was remarkable. Sports medicine, I mean, Bernie Witkin, 91, is reading law review articles on sports medicine, legal issues in race and sexual orientation, air pollution. It was remarkable.

About eight years ago, when I was having a momentary doubt about how rude I was being to the judiciary of California (Bernie said it wasn’t rude enough, but I don’t know whether that was true), I went to visit him at his house for counseling. And I said, "Oh, great guru, Bernie Witkin," you know, this whole routine. By the way, at what age in your life do you stop being a pain in the neck and start being a guru? It’s a question I’ve always had. Anyway, Bernie had a style about him. You’d ask him a question, something you really wanted to know, and he would never, ever answer the question the way you were hoping he might. So he said, "Come on. I’m gonna show you my house." So we wandered through the house and he said "Here are the rooms," and he showed me "Oh, here are the frogs. Here are the frogs. Here are the Gilhooly frogs. Here are the hanging frogs. Here’s the Thomas Jefferson frog," all sculptures of funk art with which I was familiar. And then he says, "Come on, I’m gonna show you my wine cellar." His pride and joy. And so you walk downstairs into, in contrast to his office which is low tech, his wine cellar, which was everything but low tech. And he says, "Look at this." He says, "Isn’t it terrible?" And I was frankly startled because it was pretty elaborate and pretty big. But there were some shelves that were empty and he said, "Oh, my doctor told me I had to stop drinking." And for years after that he grumped and complained about the fact that he couldn’t drink his wine. And he said, "But Phil, here’s the answer to your question." And I said, "Oh, okay." And he says, "I’m going to be buried right here. Right here." I mean I had gone to the man for advice, for counsel. What happened to this? "I’m gonna be buried right here." Alba told me later that this was part of his routine. He also wished to have a life-size bronze sculpture mounted right outside the house and I don’t know whether that’s going to happen.

He loved the law, even though, as the Dean indicated, he didn’t like law school. He hated the Socratic method. Zinged Harvard’s instruction technique every time he could and did it as long as he lived. He loved the law. He loved the judges of this state. He loved the courts of this state. No matter how much he hectored and teased them, and he did it unmercifully. I picked a couple of citations out of Bernie’s speeches, to give a little flavor for those of you who’ve not been exposed to Bernie Witkin and what he would say to judges. He gave a speech repeatedly which was usually titled "Justice `a la Carte." It was occasionally titled other things but it was usually "Justice `a la Carte." He also wrote his own poems. God knows he did not receive the Poet Laureate of America designation for his poetry, but given the state of legal writing, anything that seems like a sense of humor is such a marvel that we ought to be pleased by receiving it. Here’s a short Witkin poem addressed to the judiciary of California: "Jurisdiction is a many splendored thing. It makes the law do damned near anything. It’s the legal system’s reason for being the gimmick that makes each judge a king. Once upon a high judicial hill, seven judges huddled and had a spill. Oh happy court, you’ve had your fling and jurisdiction’s now a many splintered thing."

For his charm, his stories, the generosity that he and Alba have expressed so many times, and for his professional work, Bernie remained for me at the end a man of self-possession, but unassuming. A charm to be with. Tolerant in many ways of the world, even of politicians. And it seems appropriate to quote the only thing I’ve found as I was going through many of his speeches that might have been an epitaph for him. He wrote it himself. He was off speaking to the predecessor of Deering’s Code, I don’t know, somewhere in the Middle West, and this is 1964. His speech was 49 pages long. Castro-like in length I thought. But at the end of it he rewrote Shakespeare—without credit by the way. I thought that was interesting. He had these lines and I’m going to kind of remember Bernie this way: "Soft you now, the silenced Witkin leaves. Boys in all your horizons may all my distant masts be seen." Thank you very much.

JUSTICE NORMAN L. EPSTEIN: Thank you, Assemblyman Isenberg. One of the most distinguished lawyers in California, Seth Hufstedler, is past President of the State Bar of California and holds any number of other dignities. He is also a longtime friend of the Witkins and he brings the particular perspective of a practicing lawyer to Bernie’s career. Mr. Seth Hufstedler.

SETH HUFSTEDLER: I do think it is appropriate that we hear from a lawyer today. All of these gentlemen and ladies to my left have gone on to greater things, but there are still some 130,000 lawyers out there in California practicing law today. I was reminded by Phil’s comments on Bernie’s collection of materials for 1996, of an event which I thought illustrated Bernie just about as well as anything that I remember from him. Bernie frequently stayed with us when he was in Los Angeles. He was staying at my house at the time, and oddly enough we were standing at the bar, but Bernie had a drink in his hand, not on his head. And he said, "You know, Seth, I’m 80 this year." And I did know that, as a matter of fact. And he said, "I’ve been thinking for some time that my books need rewriting. And so I’ve laid out a five-year program and I’m going to rewrite all of my books in the next five years." Now you know, when I get to be 80 I’d kind of like to have a 5-year program that I could look forward to like that. But the interesting thing is, Bernie did precisely that. It took exactly five years and he did rewrite all of his books. It shows the kind of dedication, the kind of energy, and the kind of enthusiasm that he had.

Now lawyers in California have long since put Bernie on a pedestal, with very good reason. In California, we probably have quite a few lawyers who don’t know Blackstone from Blackacre. We probably have quite a few that think Coke on Littleton had something to do with a drug bust. And certainly there are quite a few of them who don’t know anything about the Code of Justinian. But every last one of them knows Bernie Witkin. Now it is true that many of them think he is, as Phil indicated, an institution. But they have been so pleased, and I’ve seen it happen through the years, for people to realize that Bernie Witkin was a living, breathing human being. Warm, generous, funny, and someone they could really like and respect. And the result was he had this huge wave of affection and adulation from lawyers, that it didn’t matter where he went. And it’s true he wanted to be the center of attention, but he rarely had to vie for it. It just came to him naturally because of what people thought about him.

There’s one contribution that Bernie has made to the State of California which I think we sometimes are inclined to overlook. It isn’t as apparent as it might be. Bernie has put the law of California into its most accessible form. There’s no place you can go, any jurisdiction, any place in the world, where you can find the law when you want to get to it with the accessibility that you can find it in Witkin’s work. And the result of that is a long-term benefit to our entire state. It provides a stability and a uniformity to the law that other jurisdictions can’t get quite so easily. They may have to go out and look at a dozen code sections and read 50 cases, and everybody doesn’t do that. But here we have one good clear-cut standard built with integrity that we all accept and that has been consistently used in California to keep the law going in the right direction and in a consistent form. And stop to think for a moment of the literally millions of hours of research time saved by thousands of lawyers, and conversely, or as a corollary let’s hope, savings of fees to clients because they could find the answers without spending all of that time in the library.

I’ve had the very happy experience of working with two of the country’s, the world’s, finest appellate lawyers. One of them is my wife, Shirley, whom most of you are acquainted with. The other is Otto Kaus, who, as you heard, unfortunately just passed away two days ago. Otto was a great friend and admirer of Bernie’s. We frequently talked about Bernie. I’ve frequently talked to Bernie about Otto, you know, talking about friends is a lot of fun. But I had the happy experience of having an office with Otto’s office there and Shirley’s office there. And I will tell you to have that experience for several years is a wonderful way to practice law. And time and again—I can’t tell you how many times—I would walk into one office or the other and say, "I’ve got a question here I want to ask you about. What do you think about this?" And without answering either Shirley or Otto would turn around, pull out a volume of Witkin, and start looking through it, because they always had a full set of all the civil volumes of Witkin in their offices within arms’ length. And I will tell you most really experienced practicing lawyers in the appellate field will have all of those sets right in their offices. Not down the hall in the library. Right in their offices where they can put their hands on them.

You’ve heard a lot about Bernie’s contributions and Bernie’s and Alba’s philanthropies. But there’s one that I think most lawyers don’t know about and I would like to mention it to you. It was about 25 years ago that Bernie began getting enough money to get ahead of things and he thought he ought to give some of it back to his profession. And so he created a foundation. The Foundation on Judicial Education. Set up some trustees on it. Gave it a good chunk of his own money. And that foundation exists today and has been using the money for development of educational materials for judges. The benchbooks that are circulated to judges are paid for by the Foundation. Bernie has given most of those proceeds that come from public sale of those books to the Foundation for continuing use.

Well, there are a lot more things to say about Bernie. Alba will tell you some of the more important things in a moment. We probably can’t do more than reflect on what a great guy Bernie was. I’ve often wondered why Bernie was so successful. Two things occur to me that are significant, entirely apart from his being a wonderful human being. You know, a lot of very bright people do great things and they’re not wonderful human beings. Bernie was. But probably the most interesting single thing about Bernie is that he made a unique intellectual contribution to the law. And I mean genuinely unique in the literal sense of the word. Not this more or less unique stuff. Nobody has ever done what Bernie did. And I predict that nobody will. A lot of people have tried. A lot of people have thought in other states, how can you have all of this and we don’t have it in our state? And it never happens because they haven’t found somebody with Bernie’s talent to do it. So what Bernie did and what I wish I could say we all did here, and I doubt that many of us have done it if at all, is: he created his own place in the world. He’s the only man or woman who’s ever done that. He may be the only man or woman who ever does it. And not only did he do it, but he did it with brilliance and grace and became the most successful legal writer of all time. There won’t be another Bernie Witkin.

JUSTICE NORMAN L. EPSTEIN: Thank you, Mr. Hufstedler. The generosity of Bernie and Alba Witkin has only recently become a matter of public information. Only the Witkins had any idea of how enormous is the number of persons who have been touched by their gifts. Among the beneficiaries is any judge who has sat on a California court anytime during the last 30 years. Another is the Lamplighters, the Bay Area’s own Gilbert and Sullivan company, whose orchestra you heard as you came in and which you will hear again a little later. The Witkins’ contributions at a critical time saved the music program in the Berkeley city schools. And there is much, much more.

Many of the persons the Witkin have helped will go on to help others or to grace the lives of people in other ways. The next person I shall present is one of these. A couple of years ago Alba heard a magnificent new voice at recital at a young musicians program at the University of California, Berkeley. She told the director that this was a talent that must be encouraged and professionally trained, and that she and Bernie would be pleased to help. That young musician now holds a Witkin scholarship and is a student at the Cleveland Institute of Music. Her name is Jeannine Anderson, and I am sure you will hear her name and her voice in the years ahead. She’s going to sing the aria that so moved Alba. It is Il Mio Babbino Caro from Gianni Schicchi by Puccini. She’ll be accompanied on the piano by her teacher, David Tigner.

JEANNINE ANDERSON sings.

JUSTICE NORMAN L. EPSTEIN: Thank you so very much. That was gorgeous.

Ladies and gentlemen, Mrs. Alba Witkin.

ALBA WITKIN: I’m touched by your presence. I’m warmed by all of you being here. Bernie Witkin was unique. He was a one and only and he’s all of the things that you said he was. In your notes to me, there’s a recurring theme that you thought he was going to live forever. And he thought so too. He had a dream and it was almost brought into creation before he died. And I’m going to announce to you right now that you will hear about this dream very shortly. Bancroft-Whitney, his publisher, is going to release the details of the Witkin Legal Institute, a separate entity that will carry on Bernie’s works: his publications, his books, his CD-ROM’s, and all the ways that Bernie had an impact on the California legal and judicial system. The Institute will attempt to carry this on. Under Bernie’s tutelage a core of senior attorney-editors learned to fashion words in the way that Bernie wanted them to come out. And they will continue to do this with diligence and competence and with great skill and ability. They will be supported by a staff of people all of whom now form the Witkin unit at the Bancroft-Whitney publishing company. And so indeed, Bernie’s legacy will carry on. He will influence lawyers. He will have an impact on judicial matters, especially judicial education. And so Bernie will continue. He will live on. And I thank you all very much for being here today to pay homage to a very great man. Thank you.

JUSTICE NORMAN L. EPSTEIN: I hope Bernie has been listening. He’s probably up there reorganizing things, restating them in a more understandable form. Jabbing his finger at an angel and telling a story that may shock an angel, and relishing the story himself with that wonderful laugh that was unique to him. Not long ago Bernie was asked what advice he would give to a young man or woman thinking about entering the law. This is what he said:

BERNIE WITKIN: I would say don’t do it unless you have a passion for it. The glamour is mythical. It’s hard work. It’s unremitting work. The joy is in getting out of some rut that you’re in, in some area which has no intellectual or emotional content. And here you’re getting into something which challenges all your mental resources and all your emotional feelings and all your social consciousness. And it is exciting, but if it isn’t exciting and you’re not going to sacrifice for it, sacrifices in time and effort, don’t do it. But if you do go with that intention of savoring all of these blessings, you will never regret having done it. But now we come back to what I think was your intended statement. Someone who has passed the bar and is ready to practice law. And I would say, welcome to the largest Bar Association in the civilized world. And we know that is true with our enormous number of lawyers all parts of the State Bar, sometimes called the State Bar Association by outsiders. And I would then say you are now in a position with the authority to engage in professional services to earn a living for yourself and for your family. And there’s nothing wrong with that, if you can get the business. But that’s the least important of what is happening to you. You will be invited by the bar organizations to participate in the great crusade to bring the 19th and 20th century system with all of its defects into the 21st century in a shape which will make it endure to carry out its objectives of protecting our democratic freedoms and our free enterprise system. And I will say there will be a lot of excitement, a lot of fine associations, a lot of stimulus, and the rewards of having been a part of this great movement.

JUSTICE NORMAN L. EPSTEIN: Thank you for being here, and thank you for being a part of Bernie’s life. We are adjourned.

(Derived from Supreme Court minutes and 13 Cal.4th.)