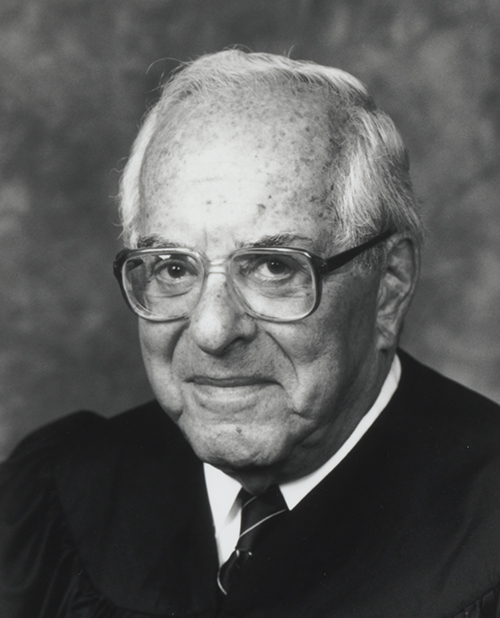

Associate Justice

September 1964–June 2001

In Memoriam

Judge of the Superior Court of Los Angeles County (1943 – 1959)

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the State of California (1964 – 2001)

The Supreme Court of California convened in the courtroom of the Earl Warren Building, 350 McAllister Street, Fourth Floor, San Francisco, California, on September 4, 2001, at 9:00 a.m.

Present: Chief Justice Ronald M. George, presiding, and Associate Justices Kennard, Baxter, Werdegar, Chin, and Brown.

Officers present: Frederick K. Ohlrich, Clerk; and Harry Kinney, Supreme Court Marshal.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the September session of the California Supreme Court.

We meet today to honor Justice Stanley Mosk, who served with great distinction as an associate justice of this court from September 1, 1964, until his death on June 19, 2001. Today is the 89th anniversary of his birth.

Early last year, Justice Mosk set a record for length of service on the court, which memorialized that event with special proceedings published in the court’s official reports. Justice Mosk’s tenure of almost 37 years æhe would have reached that milestone three days agoæis extraordinary not only for its length, but also for its outstanding contributions to the jurisprudence of California.

The court and the entire state have been immeasurably enriched by Justice Mosk’s remarkable service, that spanned almost one-quarter of the 151 years of California’s statehood and of the California Supreme Court’s existence. Indeed, the impact of Justice Mosk’s career has been national in scope.

On behalf of the court, I wish to welcome Justice Mosk’s family, staff members, and friends I will now introduce the members of the court. To my immediate left is Justice Kennard, and to her left is Justice Werdegar and then Justice Brown. Seated to my right is Justice Baxter, and then Justice Chin. Justice Mosk’s seat, to my immediate right, is vacant. We await the Governor’s appointment of a new associate justice who will follow, but cannot replace, Justice Mosk.

I first met Justice Mosk when he, as Attorney General of California, hired me fresh out of law school to join the California Department of Justice as a deputy attorney general. He soon left that position to join the Supreme Court, where, over the next seven years, I presented oral arguments before him as I represented the State of California. After I joined the bench, serving as a municipal and superior court judge and appellate court justice, I frequently looked for guidance to the opinions authored by Justice Mosk for the Supreme Courtæand experienced some apprehension when a case he and his colleagues were reviewing had arisen in my courtroom. He had a sometimes disconcerting way of dissecting decisions that had seemed perfectly reasonable at the time they were made. Whatever the conclusion reached by the high court, when you read an opinion he had authored you knew you would learn a great deal.

When I was elevated to the Supreme Court, it was readily apparent what a privilege it was to serve with Stanley Mosk. I took great pleasure in having the opportunity to consider weighty legal issues with a man who had been so constant a force in my professional life, and particular pleasure in our becoming close friends.

After Justice Mosk’s death, Charles Vogel, Administrative Presiding Justice of the Court of Appeal for the Second Appellate District, sent me a copy of an article that Justice Mosk had written in 1983. The article struck a chord for me as I thought about its author and his impact on our courts.

Entitled Eulogy for a Robe, this article was a tribute to the robe that was presented to Justice Mosk by his assistants at the Attorney General’s Office when he left to join the Supreme Court. The robe was more than 18 years old when Justice Mosk took leave of its frayed collar and ragged sleeves. He used the occasion to reminisce about the great California justices with whom he had shared the bench while wearing this garment, and about the historic occasions in which he and the robe together had taken part. He observed that “the black garment listened to arguments in cases involving death and cases involving fortunes, matters concerned with constitutional rights and those affecting the pattern of the law in every known field of legal endeavor and some previously unknown.”

Justice Mosk’s nostalgic description of the career of his robe in a way serves to sum up his career as well. But unlike the robe, he was always far more than a passive participant and remained throughout his life actively engaged in shaping the law and, ultimately, the society to which he dedicated his life.

The judicial opinions he authored covered the vast expanse of subjects the law may affect. This legacy will long provide guidance for the development of the law, not merely because of the volume of the jurisprudence created by Justice Mosk, but because of its quality and insight.

We at the court will deeply miss Stanley Mosk as a friend, as a colleague, and as a jurist.

Several speakers will comment today on various aspects of Justice Mosk’s life. It is first my pleasure to introduce Richard Mosk, Justice Mosk’s son, a noted attorney in Los Angeles who also serves as a judge on an international tribunal at the Hague.

MR. RICHARD MOSK: Chief Justice George and Associate Justices, may it please the Court: Pericles in his famous funeral oration said, “The truth is that the eulogy of others is only tolerable so long as the hearers feel that they could each have risen to the occasion had the part fallen to them.” I am sure Stanley Mosk’s colleagues here could have risen to the occasion. With that assurance and my promise not to repeat my earlier published descriptions of my father’s interesting and productive career, I hope the following will be tolerable.

Felix Frankfurter once wrote to a young boy interested in the law that, “No one can be a truly competent lawyer unless he is a cultivated man.” He went on, “Stock your mind with the deposit of much good reading. Widen and deepen your feelings by experiencing vicariously as much as possible the wonderful mysteries of the universe. . . .” Stanley Mosk, throughout his life, did what Mr. Justice Frankfurter recommended.

Stanley Mosk had no strong attachment to any ethnic community and was not raised with strong religious training. So in this sense, as Hellenic historical writers, he was not bound or shaped by any external traditions. He was, of course, affected by the interest his parents had in literature and public events.

He did not seem to mind being labeled a “liberal,” or even having certain of his decisions described as anomalies for a liberal. To him, the liberal outlook was that which allowed people to develop themselves as freely as possible – with restraints on the state or, if necessary, with the assistance of the state.

His liberalism entailed what Justice Frankfurter said was “an allegiance to the human and gradualist tradition in dealing with refractory social and political problems. . . .”

I might add that the few judicial opinions that some have characterized as contradicting his “liberal” philosophy, or as reflecting some adroit recognition of political realities or perils, in fact represented long-held views that were consistent with his earlier works and pronouncements.

Stanley Mosk believed that the protection of individual rights and the remedying of social and economic unfairness were in the best interests of society. Accordingly, while working for Governor Culbert Olson and as Attorney General, Stanley Mosk attempted to carry out these goals. He was awed by the power of the Attorney General to use the laws for the general welfare. As Attorney General he could and did strike blows against intolerance and support the public interest. But, as a judge, although mindful of public policy, he recognized the limits on what he could do.

Justice Mosk believed, as Mr. Justice Goldberg said, that, “the Constitution contains a built-in prejudice in favor of the individual.” Stanley Mosk wrote, “that the Constitution is not a set of neutral pronouncements. It is structure of law implicit with values–moral values, civic values and social values. It takes sides–always on the side of the individual, guarding his security, his dignity, his claims to equal and fair treatment, against the ponderous demands of the collective state.”

It may come as a surprise to some, but he said that he “consider[d] [him]self to be a federalist” because he believed that “our Founding Fathers created a limited national government.” By that he meant, “An American is permitted to do everything except that which is prohibited, and the permissible prohibitions by the federal government are limited. ” And of course he believed in the vitality of state Constitutions to the extent they provided protections and rights that had not yet been determined to be guaranteed by the United States Constitution.

Justice Holmes, when on the Supreme Court of Massachusetts, wrote in 1897, “I think that judges themselves have failed adequately to recognize their duty of weighing considerations of social advantage.” Justice Mosk recognized and fulfilled this duty. Most thought of Stanley Mosk as an eminently reasonable person, but perhaps not. As George Bernard Shaw wrote: “The reasonable man adapts himself to the world. The unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.”

Stanley Mosk’s good friend Chief Justice Earl Warren was once described as “a person without rancor, tension or bitterness; even his political adversaries like[d] and respect[ed] him.” The same could be said of Stanley Mosk. I submit that these attributes, although not calculated, contributed to his success and contradict the adage attributed to the famous baseball manager Leo Durocher that “nice guys finish last.” It is true that Stanley Mosk was regarded rightfully as a great intellect and able; and he had good fortune in his career. My mother, Edna Mosk, was not only a loving wife and mother, but contributed great energy, wisdom, and political fundraising prowess to advance his interests. But these factors by themselves cannot explain completely a span of 70 years of undefeated electoral contests – from election as high school class president to reelection at the age of 86 as a Supreme Court justice for a 12-year term and appointments, offered appointments, and promotions by the highest political officials. The fact is, his personality had much to do with his attainments. I point this out only to demonstrate that the road to success in politics and the law – and maybe even in life – need not be grounded on blind ambition and ruthlessness. Stanley Mosk demonstrated that respect, loyalty, friendship, amiability, and character all count. Some, such as Professor Stephen Carter, contend that “it is morally better to be civil than to be uncivil.” This is true, but civility also has its rewards.

Stanley Mosk, at times, did seem to have a pessimistic view of the development of society. He often lamented that when our country was founded, a small pool of inhabitants produced so many “cultured, articulate, [and] intellectually brilliant” leaders, but now, with a population more than 100 times larger “we search in vain for leadership of that quality.” He went on to quote Archibald McLeish, “’Where has all the grandeur gone?’”

In one case he wrote, “Unfortunately morality appears to be a waning rule of conduct today, almost an endangered species, in this uneasy and tortured society of ours: a society in which sadism and violence are highly visible and often accepted commodities, a society in which guns are freely available and energy is scarce, a society in which reason is suspect and emotion is king. Thus with a feeling of futility I recognize the melancholy truth that the anticipated dawn of enlightenment does not seem destined to appear soon.”

He decried many suggestions for “reform,” as, in reality, threats directed at the independence of the judiciary. Almost 25 years ago, he mourned the status of the legal profession when he said,“Until the final third of the twentieth century, lawyers and judges were respected in society for their learning, their integrity, and their devotion to the lofty principles of a profession which is itself built upon learning, integrity, and principle. Since a concatenation of circumstances caused the profession of the law to plummet from near heights a decade ago to near depths today, we now require a period of introspection.”

I maintain that in reality he recognized that the past was not so idyllic and the present not so discouraging. Indeed, it has been said that “[v]irtually every lawyer and writer in America reviewed the changing nature of [the] country with alarm.” I do think he was somewhat like Mr. Justice Brandeis, who, hated “the mechanization of life.” He particularly deplored actions and words of leaders calculated solely by public relations. He would agree with Judge Learned Hand who said, “A great people does not go to its leaders for incantations or liturgies by which to propitiate fate or cajole victory; it goes to them to peer into the recesses of its own soul, to lay bare its deepest desires; it goes to them as it goes to its poets and its seers. And for that reason it means little in what form this man’s message may have been; only the substance of it counts.”

His seemingly bleak view of society did not affect his own psychology. He had the same feeling as did John Adams, who wrote to Thomas Jefferson late in their lives, “I have never yet seen the day in which I could say I have had no pleasure; or that I have had more pain than pleasure.” Perhaps his long life that was generally illness free was a result of genes, but I suspect that his great satisfaction with his work, his outlook, and his ability to resist unnecessary conflict, anger, and stress played major roles.

Again, his favorite philosopher, Woody Allen, had the solution to our problem. Allen observed that “More than at any other time in history, mankind faces a crossroads. One path leads to despair and utter hopelessness. The other, to total extinction. Let us pray we have the wisdom to choose correctly.”

In his resignation statement, the transmission of which was interrupted by death, Justice Mosk expressed his gratitude to the people of the great state of California for giving him the honor, privilege, and opportunity to serve. Justice Mosk’s family also expresses its appreciation to the people of California; to the members of this court for the respect, support, and friendship they have accorded him; to his loyal and productive staff; and to the thoughtful and efficient support staff of the court and related state agencies.

People like Stanley Mosk deserve honor because they surpass the accomplishments of their predecessors. His expectation was that his own wisdom will be transcended by those who succeed him. I hope that the inspiration to do so will be his legacy.

Stanley Mosk lived as long and as productive a life as one could hope to live. His life was not only a gain to us who loved him, but also to the world. It was a rich life that ended surrounded by honor, respect, and love. Thank you.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Thank you very much, Mr. Mosk.

It is now my pleasure to introduce former Associate Justice Joseph Grodin, who served with Justice Mosk on the Supreme Court and now teaches at Hastings College of the Law. I’m also pleased to see with us today former Associate Justice Cruz Reynoso. Now, Justice Grodin.

JUSTICE GRODIN: Honorable justices, family, and friends of Justice Mosk: It is a personal honor to be asked to participate in this memorial, as it was an honor to serve with Justice Mosk during my comparatively brief period on the court, and I must say it comes as a personal shock to me to see the court for the first time without Justice Mosk.

If there were a hall of fame for state Supreme Court justices, as there is for baseball heroes, Stanley Mosk would be there. I doubt that any knowledgeable person would disagree. But it is worth asking, I think, why this is so. What is it that makes a few judges stand out above all the rest, present company excepted of course, so that we think of them by general consensus in terms not simply of competence, but of greatness?

I’m certain there is not one answer to this question, and equally certain that people of differing philosophies as to the nature of law and the role of courts would disagree about what the answer is, but let me try my hand.

I like to think of the law as a great edifice, a cathedral, a temple if you like, constructed over time, always a work in progress, ever-changing in design, an edifice that provides shelter to our most cherished liberties and our most valued community ideals.

All of us in the legal community are part of that grand project. The lawyers who provide the building materials in the form of arguments, information, and narratives, and the judges who select and mold the materials to provide symmetry and continuity and function, each decision contributing to the integrity of the whole.

It is a project that requires skilled craftsmen, and Stanley Mosk was a craftsman par excellence. He cared deeply about the judge’s craft, about the way the law is made. He careed about collegiality within the Court; and while his numerous and personally crafted dissents were typically sharp and vigorous, they never interfered with genuine cordiality.

He cared about the language of the law. On one occasion in which he agreed entirely with the court’s reasoning and holding, he wrote separately to object to the court’s use of the term “gender discrimination” instead of “sex discrimination,” insisting, quite accurately, that gender has to do with words not people. A short time later I received in my chambers an issue from the University of Chicago Law Review devoted entirety to what the editors called “gender discrimination,” and, to tease Stanley, because I knew he had attended Chicago Law School, I knocked on his door and took the issue in to show him. A short time later, there he was seated at his ancient typewriter, pecking away at a letter to the editors of the law review, protesting their egregious misuse of the term “gender discrimination.”

But the law’s project requires not only skilled craftsmen, it requires architects. It requires judges who are capable of perceiving how the particular case and the particular issue fits into the overall structure of the law; or, more broadly, as the legal philosopher Ronald Dworkin would say, how it fits within the framework of institutions and values that define our political community.

These are the judges, few in number, whose opinions we remember for their enduring contributions to the structure of our jurisprudence. Stanley Mosk was one of that breed.

Whatever the issue, whether racial discrimination in jury selection, or the impact of hypnosis on the integrity of the factfinding process, or the distribution of liability among multiple producers of a dangerous product, or the protection of workers against the misuse of arbitration agreements, Justice Mosk viewed the court’s role in broad terms, not as simply deciding a particular controversy, but as providing a blueprint for the future.

In issues involving the common law or the interpretation of statutes, he was not inclined to take cover behind the shibboleth, leaving the issue to the legislature, because he understood that could be an excuse for avoiding judicial responsibility.

Nationwide, he was a leader in recognizing the independent character of state constitutions and the enhanced potential for protection of human freedom that state constitutions can provide. And in the consideration of constitutional claims, he was consistently forthright and courageous in asserting the independence of the judicial role.

Frequent mention is made of Justice Mosk’s record longevity on the court, and that is indeed a remarkable accomplishment, but the truth is there are judges who served for many years whose names we scarcely remember. Justice Mosk’s name will be remembered by future generations of lawyers and judges and students of the law as that of a master builder, one whose contributions to the temple of the law were both beautiful and enduring.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Thank you very much, Justice Grodin.

I now would like to introduce Mr. Joseph Cotchett, a prominent legal practitioner in the Bay Area who was a friend of Justice Mosk’s.

MR. JOSEPH COTCHETT: Thank you very much. Chief Justice, other associate members of the court, and friends, I come here not as a justice and judge, I’m not as eloquent as Justice Grodin in pronouncements of the law, but I’ve been honored to be asked to speak just for a few minutes, as a friend, and as a simple lawyer that followed Justice Mosk’s career.

I don’t have to go through his career, no one does because everyone who’s here obviously knows the background of Justice Mosk. I first met Justice Mosk in 1958 when he was a supervisor court judge. I was a very young engineering student at Cal Poly. I formed a group called Students for Kennedy. That was in my radical days. Stanly Mosk, notwithstanding his judgeship on the superior court, came to our very first meeting. He was very interested, as you know, in the body politic. From that day forward, we became instant friends.

As I’ve said, I was a very young student. I was an engineering student and he actually said to me, “Have you every thought about law school?” I did. In fact that was one of the reasons that I went from engineering into law. Notwithstanding my interest in politics, which brings students into the law, it was this person who had such a buring desire for justice who talked to me about something other than about physics or chemistry, and showed to me what the law was all about.

When we talk about profiles in courage and we look back at that period in California, we have to remember that it wasn’t until after World War II that the state truly became a beacon for our society. We know that we had on the books, for example, in the 1950’s, anti-miscegenation laws. Our record on civil liberties and progress was not a model for the future at that time, but we had people – like Stanley Mosk – who were willing to stand up and say what had to be said.

Remember, in that period of time, we had recently put people in internment camps, and we had restrictions on the deeds of land, so that people could not buy houses.

When people describe Justice Mosk and his 37 years on the court, they talk in terms of his judicial decisions. They’ll cite to you Wright v. Dye. I think he was 31 or 32 years old when he wrote that decision striking down restrictive covenments in deeds as a superior court judge. I think it was in ’47. I’m not sure. He wrote that decision referring to the un-American concept of covenants in deeds saying that because of the color of your skin, you couldn’t own a home. This was all before the United States Supreme Court did the same thing.

They will cite to you Bakke. They will cite to you Wheeler. They will cite to you Lynch. They will cite to you these landmark cases he authored that moved our society forward.

But let me say to you that as a lawyer, as important as these decisions were, it is not the decisions that I remember him well by, it was his great courage.

I remember the short five- or six-year period that he was Attorney General. I had just gotten our of law school and he asked me if would I consider coming into the Attorney General’s Office. Tragically–and making a very big mistake–I said no, because I had just gone with a firm and I had my sights set on what I wanted to do. And, of course, as you know, he shortly thereafter left for the bench. I think that was ’65, if memory serves me. I’m getting old. My gray hair belies my age.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: You’re off by only one year.

MR. JOSEPH COTCHETT: One year.

I at least had the opportunity of bringing him as Attorney General to give a speech at Hastings Law School. And there I was sitting in the front row. I was so moved by the eloquence of his words, and I was so moved by what he did.

As Attorney General he did things that today people might take for granted as just being there, but in fact they were not always there.

He started a secion called Environmental Law when “environmentalists” were still known as “conservationists.” Very few people had idea of what environmental law was all about, but he knew the importance of the water and the air we breathe, as well as the land we look at, the beautiful, magnificent sites of California, and he started that section. I think you, Justice George, were in the office at the time and you know the new dimensions he brought to that office.

He started a section on constitutional rights back when individuals had to look to Washington for protection. His concept was perhaps this office can give some protection to citizens of California under the State Constitution.

He started a task force on voting rights when people were still figuring out how to get people to the polls to register, let alone exert their rights after they were registered.

He started a section, revolutionary at the time, on consumer rights, when caveat emptor was still a mantra of the day. And this section I remember very well because I had talks with him about it and Charlie O’Brien, his first chief assistant, about it.

He prosecuted black market baby operations in Los Angeles, which many people said were legal at the time. He went after them.

And before gun control was an issue that we all speak about, he had duty attorney generals investigating what was then called the “new wave” of zip guns in Los Angeles.

This was an activist Attorney General who didn’t walk into an office and simply reside in that office. He was committed to justice.

And little known to most, he started a task force on education. It actually included the legal issues surrounding integration for the Los Angeles and San Francisco schools, because at the time we had de facto segregation here in the city, and Stanley Mosk was very concerned about what he could do as Attorney General.

Now, it takes a lot of courage to stand and write principles and put them down on paper for all to read and follow. It took a lot of courage to walk into a school in Compton, California, and talk about busing. But he showed up in that school as Attorney General, not committed to busing but committed to the issue of what are the legal principles of desegregating our schools.

All these from the man who wrote Bakke, a case that was totally consistent with everything he stood for as Attorney General but which almost cost him a good friend, Justice Matt Tobriner. I remember those discussions, those very heated discussions, about Bakke and Justice Tobriner’s opinion on it.

The man I will always remember was not only the great jurist who wrote landmark and progressive decisions, but also the courageous Attorney General who stood for principle without counting the votes, a person who acted without first doing a public opinion poll, a person who led our state law enforcement without doing a focus group of police chiefs, a person who, in the end, stood for principle above all else. He was not every tall, but he was a giant of a person.

As a final aside, I just want to quickly tell about one moment I had with Justice Mosk. It was several years ago and also present was a man I know would be here today if he were still with us, Bernie Witkin. It was down at a State Bar meeting. In those days the Judges Association used to meet with the State Bar. Stanley Mosk was on the morning program, Bernie Witkin was on the afternoon program.

We had met at about 11:30 and the three of us went to lunch. We always laughed because Bernie just used to tell jokes until you couldn’t stop him. We got on the subject of the United States Supreme Court in the 1930’s and the court-packing plan of Franklin Delano Roosevelt; and at this point Stanley Mosk took over and for the next hour recited every single opinion with full citation, almost every page, I’m sure, and the facts about the cases that reversed Roosevelt’s policies in the ‘30s. As he went on and on, I was just in awe. And the most important aspect of it was Bernie sat there without saying a word, which was truly remarkable for Bernie Witkin. Justice Mosk recited every piece of legislation and every case that dealt with it. When it was all over, Bernie Witkin looked over at him and said, “Stanley, do you know the Rule in Shelley’s Case?” I’m pleased to tell you, he said yes and recited it! Thank you very much.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Thank you very much, Mr. Cotchett. Next, I would like to introduce Dennis Peter Maio, a research attorney who worked at the court with Justice Mosk for the past 17 years.

MR. DENNIS PETER MAIO: May it please the court.

Thank you, Mr. Chief Justice, for your gracious invitation to speak in memory of Justice Stanley Mosk before this honorable court and before his family and friends in attendance.

I enjoyed–truly enjoyed–the opportunity to

serve Justice Mosk for the past 17 years, which spanned about half of his tenure on the court and almost all of my professional life. In those years, I witnessed the great judicial events of which Justice Mosk was a part, what he did on the bench, what he wrote for the reports.

With your indulgence, however, I will not speak about any of those events or deeds or words. They are well known and widely celebrated. Others have already spoken of them more eloquently than I could. Others will surely do so again. With little to add, I will not make an attempt.

I choose instead to speak of other events and deeds and words. Many of the events in which Justice Mosk participated as a member of the court were not dramatic.

Justice Mosk prepared for the weekly conference, a task that was either daunting or more daunting or most daunting depending on the number of petitions for review set for consideration. He prepared for it always, completely, and by himself, without assistance by us on his staff.

He knew that only about two out of every one hundred petitions would be granted. He had the experience to separate the few petitions that were worthy of review from the many that were not. He nevertheless considered all equally, giving each a fair hearing on its own merits, and casting his votes accordingly.

Justice Mosk authored many opinions–almost 1,700 of them–some majority, some concurring or dissenting or both. A large number, of course, deal with the greatest of issues, such as constitutional questions affecting governmental power and individual liberty, political and civil rights, life and death. They are all familiar, and need no citation. But an even larger number deal with smaller issues, the relatively mundane matters that are embraced by the law in the everyday world, rules of contract formation, tort liability, insurance coverage, jurisdictional limits, procedure and pleading and proof. He gave as much attention to the small issues as to the great, for he believed and he acted on the belief that the law was a practical human creation, a mechanism that enabled all sorts of people with all sorts of values and goals to make communal life a going concern, a successful going concern. He was pragmatic, as others have said. But he was pragmatic out of principle.

Many of Justice Mosk’s deeds and words at the court were similarly undramatic. To us on his staff, he was a quiet man, even though he had much to say. He was not at all self-important, even though he played a role that was prominent. He generally asked us for nothing, except whatever assistance we might be able to furnish, as in each case he attempted to get to the right result. Many a time, he got to a right result that was not to his liking — every time when it involved affirmance of a judgment of death, for, as all know, he was personally opposed to capital punishment. He would not change the result. Rather, he would pause, grimace, and say a word or two and then pass on to the next matter. Once, years ago, in a case I still remember clearly, I recommended reversal of a judgment of death. He nonetheless rejected my recommendation, because the result, as I soon had to admit, was wrong. He knew what he liked and what he did not. But he believed that his job was to try to do what was right. I cannot say that he ever failed.

As I close, let me recall a particular memory of Justice Mosk, or rather a particular group of memories. Nine times in the course of the past decade, the moment for execution of a judgment of death would approach. Nine times, he would be found in his chambers, reviewing a last-minute habeas corpus petition if one had been filed, doing other work if one had not. Nine times, as the appointed hour drew near, he would assemble with other members of the court. Nine times, after what had to be done was done, he would leave and make his way home. Never did he say more than a few words. His face, however, always revealed a sad recognition that he would not see this ritual end in his lifetime. More important, his presence always demonstrated a full and open commitment to the law, not only when it guided him where he would go, but also, and perhaps especially, when it took him where he would not.

To sum up Justice Mosk’s life would be impossible. To pass upon his dealings us on his staff is not: He was kind in act and generous in spirit, altogether decent in every way. In nothing could we find him wanting. For everything, for so many things, we are grateful.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Thank you very much, Mr. Maio.

Finally, we are pleased that Justice Mosk’s wife, Mrs. Kaygey Mosk, has agreed to be a speaker today.

MRS. KAYGEY KASH MOSK: Thank you, Chief Justice George, for your kind invitation to join in this memorial for my late husband, Stanley Mosk. And my thanks also to Richard and the other distinguished speakers today, for the warm and generous portraits they painted of Stanley and his contributions to the law and the people of California. For my part, I would like to share with you some special personal memories of Stanley Mosk, the man.

Although Stanley and I were married just six and a half short years, our friendship spanned well over four decades. It began when he was a superior court judge in Los Angeles. We served together on several community organizations, and, as Humphrey Bogart said in the closing line of “Casablanca,” it was “the start of a beautiful friendship.”

Our friendship continued after Stanley was elected Attorney General. During that period I was a young married woman interested in politics, and an executive of several national and international nonprofit organizations. Stanley asked me to serve on a number of advisory committees that provided him with valuable feedback on the issues of the day. It was one of the many ways he stayed in touch with the citizens of California, creating programs that opened new opportunities for hard-working people to participate in the American dream.

When Stanley and I married many years later, it was as if we had come full circle: once again I had the great privilege of talking with him about politics and human affairs, subjects always close to his heart. But this time we had become partners for life, and shared our innermost thoughts and feelings. We were rarely apart—it was as if we were joined at the hip. Let me describe a typical day in Stanley’s life from my perspective.

In the early morning I would often hear Stanley jogging or two-stepping to his own tune. When he saw me watching him exercise, he would call out: “Kiddo, I’m hungry!” I took this as a signal to prepare breakfast. He loved food–any kind of food–and was very tolerant of my limited cooking skills: Even when I burned his toast and eggs, he would exclaim, “Delicious! What a meal!”

Stanley was always careful about his appearance–not because of vanity, but because he respected his position in public life. When he was ready to go to work each day–always well groomed and wearing a nice suit–he would turn around for my inspection, and I would say: “Okay. Okay. Today you’re even more beautiful than I am.” Then his face would break into a radiant smile and he would leave the house with his usual parting remark: “Well, I’m off to make a living for us.”

In the evening Stanley would usually bring home a briefcase bulging with court materials. After changing into casual clothes, he would point to a chair next to his and say, “Why don’t you sit there while I get this reading done.” I was always surprised he could work with the television on; but it was usually a baseball or football game, and he seemed to follow it with one ear, occasionally responding to the play with a small groan or cheer. Eventually I would say, “Stanley, it’s really quite late. Let me finish the reading for you, and make the decisions, too.” He got the message: He would quickly turn off the television and snap his briefcase shut–only to open it again early the next morning to finish his work.

In addition to baseball and football, Stanley loved tennis. Most precious to him were his weekly tennis matches–he played at least twice a week until the last few years. Although known to many as a justice of the State Supreme Court, in the Mosk household he was Stanley the athlete, squeaky tennis shoes and all.

But he had a rich intellectual life as well. He was a voracious reader and devoted bridge player. He loved going to the theater and concerts, and especially the movies. He enjoyed travelling on cruises and having a good dinner in a restaurant. During dinner the waiter would often inquire if the meal was satisfactory. This would give Stanley the opportunity to make his favorite comment: When the waiter asked, “Justice Mosk, how is your dinner tonight?,” Stanley would answer with a twinkle in his eye, “It is absolutely edible!”

There was a magic about Stanley. He was a happy person, a fun person, with a contagious sense of humor, and just being around him made others happy too. He was extremely patient and tolerant: I never once heard him berate or even criticize another person. Stanley enjoyed performing wedding ceremonies for friends, and often put the nervous couple at ease by quipping, “Would you like the five-minute ceremony or the short one?”

On the court, Stanley felt a close friendship with each of his colleagues. He always respected their views, and was proud of the collegial tone of their debates.

Stanley was a strong family man, devoted to Richard and Sandy and their children and grandchildren, and no less to my daughter Leslie Kash Brodie, her husband Arthur, and their children. I recall my grandson L.B. telling me, when he was just eight years old, after a conversation with Stanley, “Man, oh man! He’s cool! Cool!”

And Stanley was deeply loyal to, and fond of, his “extended family,” as he called them–his great staff: Peter, Pat, Dennis, Rob, Judy, and Ted; his many former law clerks; and the court’s administrative staff and security personnel. All of them returned this respect and affection, because all knew from their experiences with Stanley that he was a truly kind and considerate person, a gentleman’s gentleman.

What drove Stanley to do what he did so brilliantly, day after day, case after case, for 37 years? A short time before his passing, when we were in Los Angeles for a court session, he came home after a tiring day on the bench and mused how much he loved the law–but told me it would be the last session he would attend. He had made up his mind to retire. The high standard that he had set for himself was becoming more difficult for him to maintain, and he had reluctantly concluded it was now time for him to step down–not quit, because Stanley Mosk was never a quitter.

During the past few years Stanley and I had been planning to endow a Justice Stanley Mosk Tribute Fund at Boalt Hall, but we understood that Stanley had to be retired before that project could proceed. Now Stanley’s son Richard and I will follow through with Stanley’s wish and lead the fundraising for this great legacy.

A compilation of the wisdom of great rabbis–Pirke Avot (The Teachings of Our Fathers)–asks, “who is worthy of honor?” The answer given is, “he who honors his fellow human beings.” Stanley lived a life of honoring humanity, protecting those in need, and fighting for what he believed was right. Many have spoken today of the lasting impact of Stanley’s legal decisions, and for these he was truly worthy of honor. But as a husband, a father, a grandfather, and a loyal friend, I firmly believe he was also worthy of honor, and we honor him by this memorial. If he were here, of course, Stanley would say, “What is all this fuss about? I hope it’s not for me!” But he would at least have to let us wish him a happy 89th birthday! He was so grateful to the people of California for giving him the opportunity to serve them for more than 60 years.

He was my hero, and a hero to many others as well. We will all miss him deeply–I most of all.

Thank you, Chief Justice George, for this tribute to a great man and a loving and wonderful husband.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Thank you Mrs. Mosk. On behalf of the court, I want to express how very touched and appreciative we are of your willingness to participate as a speaker at today’s special session.

I want to thank again all those who have contributed their unique and memorable remarks this morning.

In accordance with our custom, it is ordered that the proceedings at this memorial session be spread in full upon the minutes of the Supreme Court and published in the Official Reports of the opinions of this court, and that copies of these proceedings be sent to Justice Mosk’s family.

(Derived from Supreme Court minutes and26 Cal.4th.)