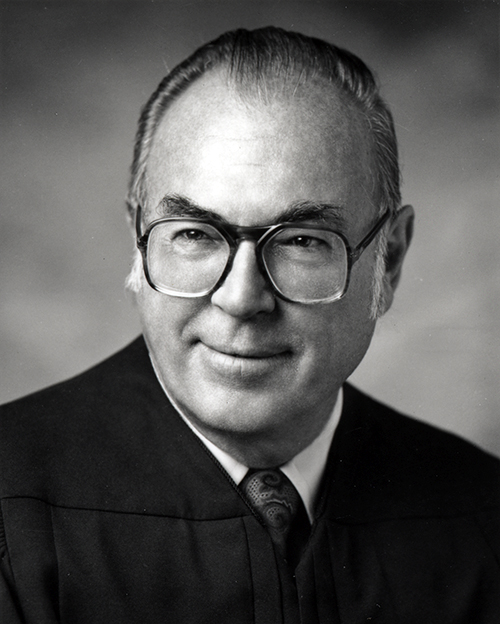

Associate Justice

July 1977–December 1982

In Memoriam

(1917 – 1996)

The Supreme Court of California convened in the courtroom of the Marathon Plaza Building, 303 Second Street, South Tower, 4th Floor, San Francisco, California, on May 6, 1997, at 9:00 a.m.

Present: Chief Justice Ronald M. George, presiding, and Associate Justices Mosk, Kennard, Baxter, Werdegar, Chin, and Brown.

Officers present: Robert F. Wandruff, Clerk; George Rodgers, Walter Grabowski and Harry Kinney, Bailiffs.

JUSTICE GEORGE: Good morning. We meet here today to honor Justice Frank Newman, who served with the Supreme Court with great distinction as an Associate Justice from July 1977 through December 1982. Allow me first to introduce the members of the court. Starting at my far left, Justice Brown, Justice Werdegar, and Justice Kennard. To my immediate right is Justice Mosk and to his right is Justice Baxter and then Justice Chin. On behalf of the court, I wish to welcome Justice Newman’s wife, Frances, his daughter, Holly, and other family and friends.

I did not have the honor of serving with Justice Newman while he was a member of the Supreme Court. I had, however, already been on the bench at the trial court level for five years when he was appointed to the Supreme Court, and so was keenly interested when he joined the court. I knew of his service and leadership on the Constitution Revision Commission, and over the years I have had many occasions to encounter and appreciate his work in that important arena.

I also have had the opportunity to get to know Justice Newman through his opinions, which I have found to be intelligent and insightful. Justice Newman’s opinions reflect his broad experience as an academic — his contributions as a teacher of the law and as Dean of Boalt Hall Law School — and his dedicated service as a champion for the advancement of human rights on the international scene.

The scope and variety of Justice Newman’s activities, before, during, and after his service on the bench reflect the breadth of the impact that a fine legal scholar may have on the development of the law.

On yet another front, I know he will long be remembered and appreciated. whether it was by continuing to encourage and mentor the lawyers and staff who worked with him during his varied career, or by playing the piano effortlessly at the court holiday party, Justice Newman was a warm and accessible presence whose support will forever be cherished by those whose lives he touched.

It is now my pleasure to introduce Dean Herma Hill Kay of the Boalt Hall School of Law.

DEAN HERMA HILL KAY: Chief Justice George, I am honored to speak today on behalf of Justice Frank Newman’s colleagues and friends at Boalt Hall. Boalt was the center of Frank’s professional life, the beneficiary of his academic leadership, and the base from which he undertook his extraordinary work in international human rights. Frank came to Boalt as a law student in 1938, graduated in 1941, returned as a member of the faculty in 1946, served as dean from 1961-1966 (the only Boalt graduate to hold that position), left in 1977 to accept appointment to this distinguished Court, and resumed teaching at Boalt following his retirement from the California Supreme Court in 1982.

An account of Frank’s impact on Boalt, and of its role in shaping his career, goes beyond the bare recital of his attendance and his service at the law school. Frank was Barbara Nachtrieb Armstrong’s student and friend, and her influence on his intellectual development was immence. As he recounted their interaction, with his enthusiastic and appreciative smile, he spoke of Barbara’s fierce and passionate attachment to her favored causes during their long arguments about the law, politics, and morals.

There was a similar passion in Frank’s own work. His interest in legislative and administrative law led to his selection in 1964 to chair the Drafting and Executive Committees of the California Constitution Revision Commission, which completed the last thorough revision of the state Constitution in 1972. Following his deanship, Frank spent a sabbatical year in Geneva, Switzerland, where he was introduced to the emerging field of human rights law. Upon his return to Berkeley, he created courses on international human rights for the law school curriculum. He stimulated the energies and enthusiasms of many of his students and junior colleagues and enlisted them in his devotion to human rights. One of those colleagues, Professor David Caron, tells us that the "Berkeley Crew," as they are known, remain active in legislative, administrative and judicial arenas in the United States and before the United Nations and other international bodies, working to emulate what David characterizes as Frank’s "unfailing optimism and faith in the human spirit."

Newman also co-authored pioneering coursebooks in human rights, including International Human Rights: Problems of Law and Policy (with Richard B. Lillich, 1979) and International Human Rights: Policy and Process (with David S. Weissbrodt, 2d. ed. 1996). But Frank Newman was not content merely to write about human rights. His vehement protests against gross human rights violations in Greece and Chile helped establish the basis for United Nations procedures to respond to such violations. He was active in and on behalf of many human rights organizations worldwide, including Amnesty International, the American Society of International Law, the International Institute of Human Rights, the United States Institute of Human Rights, the World Affairs Council, and the American Civil Liberties Union. In 1984, he was named co-chair of U.C. Berkeley’s Peace and Conflict Studies program. At the time of his death, he was offering a course at Boalt Hall on War and Other Armed Conflicts.

While Frank’s reputation rests primarily on his work in international human rights, I want to say a word about his influence on family law. His contributions to family law while serving on this Court are not sufficiently appreciated. In the interests of time, I will mention only two of the opinions he wrote for the Court, both in 1980. The first is In reMarriage of Schiffman (1980) 28 Cal.3d 640 [169 Cal.Rptr. 918, 620 P.2d 579], which replaced the traditional common law rule that a child must bear the father’s surname with a more flexible approach that resolved parental disputes about children in accordance with each child’s best interests. In arriving at this standard, Justice Newman reviewed the changes that had occurred in family law in California and elsewhere, including the enactment of the Married Women’s Property Acts, the adoption of no-fault divorce, the equalization of parental rights to custody, the elimination of sex-specific differences in property rights, and the adoption of the Uniform Parentage Act. Based on this review, he concluded that "[t]he Legislature clearly has articulated the policy that irrational, sex-based differences in marital and parental rights should end. . . .” (28 Cal.3d at 645 [169 Cal.Rptr. at 921, 620 P.2d at 582].) Justice Newman also delivered the court’s opinion in City of Santa Barbara v. Adamson (1980) 27 Cal.3d 123 [164 Cal.Rptr. 539, 610 P.2d 436], which upheld the right of an "alternate family" of 12 adults unrelated by blood, marriage, or adoption to live together in a single housekeeping unit. As a young professor who came to Boalt in 1960,1 knew Frank as a senior colleague who became my dean in 1961. I was and am grateful for his having encouraged my interest in interdisciplinary work by approving my request to teach a joint course in Law and Anthropology with Dr. Laura Nader (which required a greater effort on his part then than it would now, involving as it did his taking on the University’s dreaded bureaucracy) and by helping me obtain a year’s fellowship at the Center for the Study of the Behavioral Sciences in Palo Alto.

Frank’s talents as a pianist were put to frequent use at Boalt Hall. Throughout the 1960’s and into the 1970’s, the students presented an annual play at the end of the fall semester which usually featured a roast of the faculty. The faculty would respond with our own musical skit, words by former Dean William Prosser and later by Associate Dean Jim Hill, and music courtesy of Frank Newman. These were light-hearted occasions that contributed to the close feeling we had for each other. Many of us remember holiday parties at the Newmans’ home, with Frank playing the piano while the faculty (those who could carry a tune) gathered around to sing together. Frank’s leadership as dean drew not only on his bold ideas, but also on his genuine friendship with his colleagues.

Frank will be remembered as an innovative jurist, a dedicated scholar, an activist in the field of international human rights, and as a man who never permitted his friends and coworkers the luxury of evading the issues that concerned him most passionately.

His was a life of commitment and inspiration, and those of us who continue Boalt’s mission will always be grateful for his example. Professor Robert Cole called him "the soul of the law school." Professor John Coons spoke of his "lust for justice," and commented that "However inconvenient, his idealism never faltered. We are all the better for his intellectual and moral leadership, but even more for his simple humanity." Speaking for myself, I miss his laughter and joy which never failed him or his friends even in the most difficult times. He seemed always to know how to make things better.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Thank you very much, Dean Kay.

I would now like to introduce Mr. Guy Coburn, a staff attorney who worked with Justice Newman, and who continues to serve the court by working in special capacities even after his retirement.

MR. GUY COLBURN: Chief Justice George; Associate Justices; Mrs. Frances Newman; Holly Newman Daniels; members of the Supreme Court community; friends and admirers of Frank Newman:

I am honored by this court’s invitation to participate in today’s tribute to an extraordinary judge and legal scholar and a wonderful human being—Justice Frank Newman. My close acquaintance with him began in the spring of 1978, when to my great delight he asked me to join his staff the following September. I had been one of Chief Justice Wright’s staff attorneys and had promptly submitted my resume to Justice Newman on learning of his appointment in July 1977. Fortunately for me, one of the initial Newman staff left in 1978 to take a position with the Legislature in Sacramento. Thus began what was for me a stimulating and memorable professional relationship. After Justice Newman’s retirement from the court in November 1982, our personal friendship continued unabated until his untimely passing in February 1996.

Justice Newman had a zest for life that was contagious but difficult to describe adequately. He enthusiastically approached what he called “tough issues,” whether legal or institutional, as an adventure. His incisive mind often produced unexpected insights that made the rest of us stop short and rethink. He made all his listeners feel included, and he genuinely welcomed dialogue. He was keenly interested in the law as a tool for protecting and promoting human rights and dignity, but also was generous and empathetic at the personal level. He found real satisfaction in assisting friends and acquaintances to solve their problems or realize their aspirations. Frank Newman was the antithesis of the person who is supposed to have remarked, “I love humanity, but I hate people!” He strove mightily to promote human rights on a worldwide scale and at the same time had intense compassion for individuals.

An important source of Justice Newman’s special contributions to the court’s work was his close association with the California Constitution Revision Commission from 1964 to 1972. He served not only as a member of the commission but also on its executive committee and as chairman of its drafting committee, where he consistently proposed and advocated the use of simple, concise language. One of the revised constitutional provisions closest to his heart is found in article I, section 24: “Rights guaranteed by this Constitution are not dependent on those guaranteed by the United States Constitution.” He wrote at least three important opinions for this court enforcing provisions of the California Declaration of Rights independently of rights under federal law. In Fox v. City of Los Angeles (1978) 22 Cal.3d 792, he held that the display of a huge cross on the Los Angeles City Hall violated California’s guaranty of free exercise of religion “without discrimination or preference” and proscription against laws “respecting an establishment of religion” (Cal. Const., art. I, § 4). His opinion for the court in Robins v. Pruneyard Shopping Center (1979) 23 Cal.3d 899, construed California’s free speech and petition provisions (Cal. Const. art., I, §§ 2, 3) as protecting the right to circulate petitions to the government in a privately owned shopping center even though no such protection is afforded by the First Amendment. That decision was affirmed by the United States Supreme Court. (447 U.S. 74.) Finally, in City of Santa Barbara v. Adamson (1980) 27 Cal.3d 123, he held for the court that California’s right of privacy (Cal. Const., art. I, § 1) invalidated a city ordinance that purported to prohibit persons from living together in a family residence simply because they were not related to each other.

Justice Newman was enthusiastic about the Supreme Court’s student extern program, which was then more extensive than it is now. The Newman staff usually took on five externs each spring, summer, and fall. They worked hard and productively. We staff attorneys helped interview applicants and supervised their drafting of memos for the court’s weekly conferences. The judge himself would work with them individually, assigning them research projects or the drafting of language for calendar memos on cases being heard on the merits. About once a week the whole staff, including the externs, would all go to lunch, usually in a Chinese restaurant at a large round table. They were working lunches: we socialized, but also, the judge used them to keep all of us informed of interesting cases and issues before the court. He brought out the best in each of the externs, encouraging them to express their views and treating them with genuine respect. The Newman staff’s reputation at the law schools enabled us to select students of unusually high caliber semester after semester. That fact made the staff attorneys’ supervisory tasks much easier and more pleasurable.

In all, there were 70 Newman externs. Forty-five of them showed up at a luncheon held in August 1983 to honor Justice Newman’s service to the court. Most of the rest were absent because their careers had taken them away from the San Francisco Bay Area. The luncheon was organized by Justice Frank Richardson; about 145 persons attended, and many others sent regrets.

Justice Newman was proud of this court and much interested in its institutional problems. Thus, he developed proposals for alleviating the court’s heavy workload of automatic appeals and State Bar matters. He often included me and others of his staff in lunches with such savants as Bernie Witkin or Ralph Kleps, at which there were fascinating discussions regarding many aspects of court procedures.

I remember with great pleasure the occasional staff picnics and other social events. It was at a party in the Newman home that my wife and I enjoyed our first experience of Frank Newman, the piano player and Christmas-carol maestro. I later learned that as a teenager at South Pasadena High School he had received thorough classical musical training on the piano, pipe organ, and French horn. He then taught himself jazz piano and supplemented his four-year scholarship at Dartmouth College, in New Hampshire, by playing in a dance band. The band had gigs all over the northeastern United States and, during two summers, on steamships going to Europe. Later, while a student at Boalt Hall, he played French horn in the University Symphony.

In November 1982, Justice Newman retired from this court and returned to Boalt Hall to resume his teaching and work in international human rights. He commented that though there were many able people, particularly Court of Appeal justices, who could replace him at the court, there were far fewer who could match his potential contribution in the international area. He was particularly moved by a perceptive letter he received from an unexpected source in response to the public announcement of his retirement. It came from Justice Lester W. Roth, who had been the presiding justice of the Court of Appeal for the Second Appellate District, Division Two, since 1964. Justice Roth wrote:

“Dear Justice Newman:

I regret that a man of your demonstrated intellectual stature elects to retire from what I believe is one of the great courts of last resort in our country.

I think I understand however, how it is that one may be impelled to utilize personal talent in a field of activity which returns not only mental and emotional comfort but which also satisfies an objective to make a constructive contribution to an illusive body of law.

It is my fond hope that you will find such satisfaction in helping to truly crystallize international human rights to a status which will lead to their definition, acceptance, and to their ultimate vindication by pragmatic enforcement.”

Justice Roth’s “fond hope” for Frank Newman was clearly realized. The retired justice continued his productive efforts to enhance the scope and enforcement of human rights under United Nations treaties. Beyond that, in the words of his co-author and former student, Professor David Weissbrodt, he “taught and inspired a whole generation of human rights scholars and advocates from all over the world.”

It is hard to realize he is gone. In preparing these remarks, I could feel his warm presence and came to a better understanding of how deeply he must have touched the lives and careers of countless students, colleagues, and friends. I am grateful to him and to this court for enabling me to be included in their number.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Thank you very much, Mr. Colburn.

It is now my pleasure to introduce former Associate Justice Cruz Reynoso, who served on the bench with Justice Newman and who will speak on behalf of the court.

JUSTICE REYNOSO: Mr. Chief Justice and Associate Justices, may it please the court:

Frank C. Newman was first my teacher, then my friend, and later my colleague on the California Supreme Court.

We met over 40 years ago when I enrolled as a first year student at the University of California at Berkeley School of Law, Boalt Hall. He was my teacher in the course on equity. The law of equity symbolizes the life Frank lived. Equity seeks after fairness and justice for all. Equity seeks new ways – new forms – to assure fairness and justice. Above all, equity recognizes and respects the rights of each human being. As my teacher, Frank epitomized those qualities. He was recognized as a brilliant leader in the law school. And his relations with students were personal and warm.

In 1955, the year I joined Boalt, Frank had co-authored a case book on legislation. Though so much of the law in modern America was based on statutes, few such courses – until Frank led the way – were offered. He correctly observed in the preface that "It is in the legislative work that the profession of law has its greatest impact on law and on government." His course broke new ground – students drafted statutes (they did not just study them), met with legislators and visited legislative hearings.

Brilliance did not get in the way of gentleness. Frank invited our whole class to his house, one of the highlights of my early experience as a law student. We all felt a particular closeness to Professor Newman.

In later years, I worked for a legislator and saw first hand the importance of his legislative and constitutional work.

Frank’s interest in fairness and justice went beyond California and beyond the borders of the United States. He sought equity, fairness, and justice for all human beings who dwell on this earth. By the late 1960’s Frank became a leader in international human rights. Suffering and oppression, he felt, could be alleviated by the application of new norms, norms which sought to protect basic human rights — the right to live in peace, the right to one’s freedom, the right to one’s family, the right to participate in one’s society, the right to one’s religious beliefs — all those rights which human beings and their governments have a responsibility to respect.

The enthusiasm which Frank exhibited for the task of serving mankind’s highest ideals is engraved into my memory. When I was serving on the Court of Appeal and Frank was on the Supreme Court, I was appointed to serve as a citizen member of the United States Delegation to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, which sits in Geneva, Switzerland. Frank invited me to his chambers for a short talk about the important issues then pending before the commission. Our "short" meeting extended to the entire afternoon. Frank, Joan Pomerleau, and others and I discussed and debated those issues for several hours. Once or twice I apologized for taking so much of their time — but Frank, undeterred, sank his intellectual and emotional teeth into the next topic. I recall the great toll the disappearance of loved ones was taking in one part of the world — strangers, sometimes suspected government agents, would unexpectedly make an armed appearance, and remove a person, young or old, from the midst of his or her family. Other parts of the world suffered basic human rights violations — political prisoners in one area of the world, starvation caused by corruption in another.

Frank was not simply the intellectual. He, and a whole cadre of students he helped train, went to Geneva and all the corners of the earth to advocate for human rights From the Court of Appeal, I was elevated to the Supreme Court. The long corridor of the Supreme Court and its chambers at the State Building location, where we served, sometimes seemed to impede easy, informal discussion among the justices. By fortune, my chambers adjoined those of Justice Newman. That proximity provided us the luxury of frequent discussions about pending cases, the law, the world, or the simple but always difficult decision about where to lunch.

The Wednesday conferences, Frank more than once observed, were to him the greatest seminars he ever attended. It was at such time that the justices decided which cases would be heard. Those cases reflected the issues most important to the people of California. The constitutional wisdom of providing for seven justices was manifest. The value of the diverse backgrounds — ethnic, racial, gender, political, professional — provided the court with particular strength in making those decisions, and provided the fodder for the discussions Frank relished. I marveled that I, his former student, was now his colleague. But he never marveled. I could see that an important Newman legacy was the many former students who later worked side by side with him.

What stays with me about Frank is not his Herculean life, but his very human and humane life. It is his love for the beauty of California, whether it be the seashore and beaches of the Monterey Peninsula, or the peacefulness of the wooded Sierras where he and his family had had a rustic cabin "Forever." It is his amazement at his own changes. He had grown, he would say, from a physical "bean pole" as a young man to somewhat more robust adult, and from a small town child growing up in Southern California to a person with worldwide interests. It is his love for Fran, his joys and frustrations of parenting, and his ability to find those who could share his work.

Above all, I recall his enthusiasm for his every activity. Frank, Fran, my wife Jeannene and I shared a table with others at the annual California Supreme Court Christmas dinner just two months before his death. He was enthused about his upcoming work at the United Nations; he was enthused about the courses he was teaching; and, he was enthused about various San Francisco Bay Area law schools where he was teaching. He was enthusiastic about life.

Upon reflecting about Frank’s life, I think about some influences Frank and I did not really talk much about, but I could tell influenced him deeply. He lived through the Depression as a youngster and the Second World War as a young man. I thought about Frank when I visited the site of the recently dedicated Franklin D. Roosevelt Memorial. There we are reminded of reasons for that great war. The American people sought to protect four very basic freedoms: the traditional freedom of speech and freedom of religion. But also the freedom from want, and the freedom from fear. Those freedoms are worthy of protection in time of peace as well as war, and for all human beings.

The spirit of those four freedoms was captured by Frank when he dedicated his 1979 publication on International Human Rights: "To all oppressed people everywhere." Frank sought equity, fairness and justice for everyone everywhere. It is written that he who helps the least of us, does the Lord’s work. Mr. Chief Justice and Associate Justices, Justice Frank C. Newman spent a lifetime doing the Lord’s work.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Thank you very much, Justice Reynoso.

I want to thank again all those who have contributed their special and memorable remarks to this morning’s memorial session.

In accordance with our custom, it is ordered that this memorial be spread in full upon the minutes of the Supreme Court and published in the Official Reports of the opinions of this court, and that a copy of these proceedings be sent to Mrs. Newman.

(Derived from Supreme Court minutes and 15 Cal.4th.)