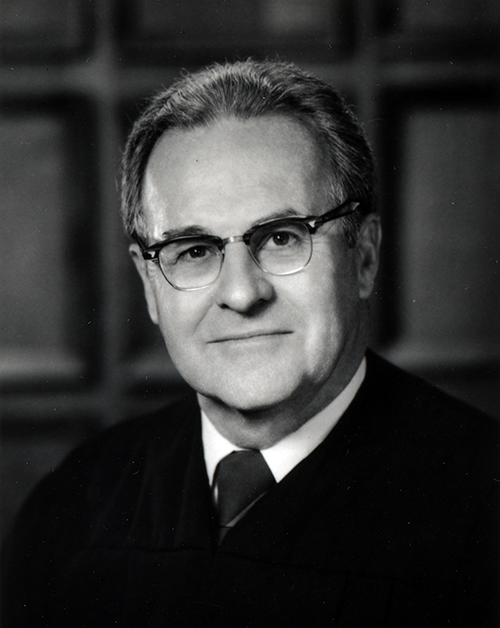

Associate Justice

December 1974–December 1983

In Memoriam

(1914 – 1999)

Presiding Justice of the Court of Appeal, Third Appellate District (1971 – 1974)

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the State of California (1974 – 1983)

The Supreme Court of California convened in its courtroom in the Library and Courts Building, Sacramento, California on Wednesday, February 9, 2000, at 9:00 a.m.

Present: Chief Justice Ronald M. George, presiding, and Associate Justices Mosk, Kennard, Baxter, Werdegar, Chin, and Brown.

Officers present: Frederick K. Ohlrich, Clerk; Brian Clearwater, Calendar Coordinator; and Harry Kinney, Supervising Marshal.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Good morning. We meet today to honor Justice Frank K. Richardson, who served with great distinction as an associate justice of this court from December 1974 through December 1983. I would like to begin by introducing the members of the court. Starting at my far left, Justice Brown, Justice Werdegar, and Justice Kennard. To my immediate right is Justice Mosk, and to his right is Justice Baxter, and then Justice Chin. On behalf of the court, I wish to welcome Justice Richardson’s wife, Betty, his children, and other family and friends.

Although I did not have the honor of serving on the court with Justice Richardson, I nevertheless had the opportunity to get to know him in a variety of contexts—at court-related events, through his opinions, and through his continued service to the court as the chair of the blue-ribbon commission appointed by my predecessor, Chief Justice Malcolm Lucas, to study the practices and procedures of the Supreme Court. These contacts served to reinforce the impression I had gained from speaking with those individuals who had been fortunate to work more closely with him: Justice Richardson approached the law with deep respect, thoughtfulness, and care, and in his dealings with others he was unfailingly courteous and kind.

During his tenure on the Supreme Court, Justice Richardson wrote a number of very influential majority opinions in cases such as Daly v. General Motors Corp. (1978) 20 Cal.3d 725, applying comparative fault principles to actions brought in strict products liability, and Amador Valley Joint Union High Sch. Dist. v. State Bd. of Equalization (1978) 22 Cal.3d 208, upholding Proposition 13, the initiative that changed California’s system of real property taxation. Many of his opinions continue to guide us today and, I am confident, will do so far into the future.

Justice Richardson also wrote many dissenting opinions, some of which served in later years as models for majority decisions of both the United States Supreme Court and the California Supreme Court. In dissent, he wrote in terms that were clear, direct, and persuasive, while at the same time courteous and respectful of those with whom he disagreed. His reverence for the law, and for the institution that he served, was evident throughout his tenure on the court.

Justice Richardson’s retirement did not end his association with the Supreme Court. As I mentioned, he served as chair of a commission appointed to study and make recommendations concerning the court’s internal procedures. These recommendations addressed almost every aspect of the court’s operations, and almost universally were implemented by the court within a few years of the completion of Justice Richardson’s report. The commission’s recommendations continue to shape the underlying structure of the court’s functions today.

With his wife, Betty, Justice Richardson was a frequent attendee at court holiday functions, and it was always a pleasure to see him there. In September 1998, I attended the wonderful celebration honoring his service to the community and to the courts held here in Sacramento. It was a pleasure to see Justice Richardson recognized during his lifetime for his many contributions. After an evening of glowing tributes, Justice Richardson responded with a gesture that for me encapsulated the warmth and directness of this fine gentleman—he ended the evening with a thank-you followed by a stirring tune on the harmonica.

Justice Richardson’s contributions to the law will live on in his finely crafted opinions, and in the model that he provided for all of us of a truly professional and engaged jurist whose commitment to family, church, and community gave his life a well-rounded completeness to which we can all aspire.

It is now my pleasure to introduce former Justice William P. Clark, Jr., who served with Justice Richardson not only on the court, but also in the national administration in Washington.

JUSTICE CLARK: My colleagues, Chief, I concur in everything you said about our colleague, Frank Richardson. In fact, your good opening allows me to reduce my own remarks, and I’ll also concur in what our great colleague, Justice Mosk, said upon Frank’s retirement. He said Frank would be recognized in California history as one of its great lawyers and judges, and I could almost sit down on that citation because I think that it covers it all, but I shall go on, having been invited to be here today.

I had the great privilege of serving with Frank, as you said, Chief, starting over 25 years ago. We served together for eight years before I moved on to Washington for other employment, and I’ll touch upon that in just a moment, as it relates to our honoree whom we are commemorating today. But Frank Richardson, in the time I was with him, wrote some 600 opinions, and I think it is an interesting commentary that less than one-third of those were majority opinions.

Frank firmly believed that law should come from the people through the Legislature, and through what he called the precious power, the precious right of the initiative process. He was critical, as we all know, of judicial law, judge-made law at all levels of the court, and said so many times.

He was not one to go along to get along. Not to suggest that he didn’t get along; there was no more collegial person on this court than Frank Richardson. But he did it through courage, through suasion and persuasion, great scholarship, and convincing others of his position. A lot of courage; and at times, of course, he was tabbed, as we all know, as politically incorrect. But that did not slow Justice Richardson down in confirming his true beliefs.

He, as I think all of us do, abhorred labels, philosophic labels. Bernie Witkin once, when confronted by some writer stating that Richardson and Clark were the two conservatives on the court, and Bernie said, “No. Wait a minute, let’s watch those labels. The two of them are predictably unpredictable, and that is good.” And then, he reminded the person, take a look at the definition of conservative. One well-known definition says, “A conservative is one who defends the status quo.” And, he said, that is not necessarily Richardson or Clark. So much for labels. Frank and I didn’t always go together. Graham remembered Agins v. Tiburon—that was six to one.

But Frank, as we pointed out, did retire from our state Supreme Court and by that time, I was at the Department of Interior, having been at the State Department and the White House. The President asked me to go and put some oil on some water at Interior. My predecessor, Jim Watt, had become the defendant on some 4,000 cases. So I turned to Dick Morris and said, “Do you think Frank Richardson might come back here and become our Solicitor, with a staff of 220.” So Frank thought he had retired, but we proved that wrong. He had 4,000 cases. He cleaned them up in a hurry. Today, when I am asked if I’ve ever been a defendant in a civil case, I have to answer truthfully, “Yes, 4,000 times.” But thanks to Frank and Dick.

By the way, Chief, if you ever do a “hallway” of former staff people, I hope that Dick and Graham over there, and certainly Peter Belton, are front and center. In that regard, Dick Morris was good enough to come up here this morning, being under pretty heavy medical treatment. He served as sparkplug to three Chief Justices, and ended his judicial career by coming down the hall for my last six years. So I want to acknowledge Dick and Graham Campbell a moment. Dick isn’t really off the court quite yet; he is still at the Thursday night court card game that, I understand, Dick usually prevails in.

In any case, Frank Richardson came back to Interior as our Solicitor, staff of 220 or 240. Within a year, most of those 4,000 cases were history. And, so for Frank, who wanted and deserved, as did Betty, full retirement, like many of us do, that was only a dream.

But I think at bottom, we’d all concur that Frank was a true gentleman and a very gentle man, who loved life, believed in the sanctity and dignity of all human life, justice and dignity, and I think he would concur in my final citation today, in memoriam, another dissent written 800 years ago, by another man named Francis. I think we can see a lot of the Frank that we talked about today in the following dissent. It is still the minority position today, but in our Judeo-Christian culture and society, we all have hope that this will prevail.

Francis wrote, “Lord, make me an instrument of your peace. Where there is hatred, let me sow love; where there is injury, pardon; where there is doubt, faith; where there is despair, hope; where there is darkness, light. And where there is sadness, joy. Lord, grant that I may not so much seek to be consoled as to console; to be understood, as to understand; to be loved, as to love. For it is in giving, that we receive. It is in pardoning, that we are pardoned. And it is in dying, that we are born to eternal life.” Thank you very much.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Thank you very much, Justice Clark. It is now my pleasure to introduce Mr. Graham Campbell, a former principal staff attorney to Justice Richardson and present member of the court’s staff.

MR. GRAHAM CAMPBELL: Thank you, Chief Justice George, Associate Justices, friends and family of Justice Richardson. May it please the court:

“The dog ate my homework.” But that excuse for being unprepared won’t work for me because I own no dog. So, my excuse today is hopefully more believable: “The previous speakers used all my good lines!” Nonetheless, I’ll try and come up with something else, but if you hear an echo in here, that is probably the reason.

Behind his back, they called him “The Deacon.” Perhaps because he was always polite and soft-spoken, always proper, collegial, even fatherly to everyone he met. Or perhaps because, after all, he was the son of a Methodist minister. Or perhaps, let’s face it, perhaps because his dissenting opinions, and there were over 200 of them, tended to be a bit preachy at times. But whatever the reason, I know the nickname was meant in an endearing way and always said with the greatest respect and affection for this remarkably talented man.

It is fitting that today’s memorial court session is held in Sacramento, a city where Justice Richardson had lived and worked so many years, and which he loved so intensely. Loved to a point that, during the nine years working with the Supreme Court in San Francisco, he unceasingly lobbied his colleagues to move the entire court, justices, law clerks, secretaries (as they were called in those less sensitive days), and everyone else, to this fair city. I believe he may have convinced Justice Clark of the wisdom of his plan, but unfortunately (from his perspective at least), the other justices remained firmly resistant. Perhaps they were skeptical, as I was, of his repeated claims that the Sacramento crime rate was the lowest in the civilized world, and that the temperature here always hovered around 72 degrees, even in July and August.

I was Justice Richardson’s staff attorney from the time he arrived in 1974 to the time he retired, nine years and 394 opinions later. I have been asked to share today a few memories about those years, and I will do that. But we all know that Frank Richardson’s life encompassed far more than just being an esteemed appellate justice. He was also a devoted family man, acclaimed legal practitioner and law professor, generous contributor to charitable causes, tireless civic leader, energetic community volunteer, and respected Solicitor of the Interior. Therefore, my remarks necessarily will cover only a small part of this great man’s varied accomplishments.

Looking back on the Supreme Court years, I’d have to say (and I think he would agree), “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” It was certainly the busiest of times. There were weeks when it seemed as if we were writing a new dissenting opinion every day. The figures show that Justice Richardson authored 394 opinions during his tenure with the Supreme Court, of which 212 were minority opinions, mainly dissents. In hindsight, I now realize that for me it was the most exciting and intellectually stimulating experience I’ve ever had. Based on the many dissenting opinions the judge wrote during that period, you would think were in a war zone. But we survived with very few battle scars, and hopefully our dissents provided some food for thought for future courts and Legislatures.

I also think it was quite an achievement for him, in addition to writing all those dissents, to have written 182 majority opinions, averaging more than 20 majority opinions for each of his nine years. These included such important and renowned opinions as Agins v. Tiburon (1979) 24 Cal.3d 266, setting the ground rules for recovery against public agencies for restrictive zoning ordinances; Amador Valley Joint Union High Sch. Dist. v. State Bd. of Equalization (1978) 22 Cal.3d 208, upholding Proposition 13, the property tax initiative; Daly v. General Motors Corp. (1978) 20 Cal.3d 725, applying comparative negligence to strict liability cases; People v. Scott (1978) 21 Cal.3d 284, outlining the outer limits of searches and seizures of physical evidence from criminal defendants; and Brosnahan v. Eu (1982) 31 Cal.3d 1, upholding Proposition 8, the Victims’ Bill of Rights initiative. Quite obviously, the man was not only just a hard worker but he was a hard worker with the rare ability to form a consensus among fellow justices with vastly differing philosophies and predilections.

Justice Richardson’s diligence, easygoing personality and keen common sense made the task of working for him largely an effortless one. More often than not, on cases he was interested in, and that included most of them, he did all the hard work himself. His staff just fed him the raw material. Of course, all our drafts were handed to him without footnotes, for he loathed them and would not permit his staff to use them. He often suspected the majority justices would use footnotes in one case to provide authority for their next case, and so on and so on, in an endless string of bootstrapping opinions. To each one of which we, of course, would, quote, “respectfully dissent.”

I was a hot-blooded conservative in those days. (I guess that makes me a cold-blooded one now!) I recall one impassioned draft dissent I gave Justice Richardson, one where I described the majority’s proposed opinion by using a lot of overheated adjectives like “irrational,” “bewildering,” and “bizarre.” He read over the draft carefully and later returned it to my office, telling me, “Graham, maybe you better immerse this one in a bucket of ice water for a few hours!” I reluctantly removed most of the adjectives. Of course, I sneaked half of them back in the next draft.

“The Deacon” kept his courteous demeanor, collegiality and sense of humor throughout these days of seemingly unending dissents, even after the departure of Justice Clark for Washington, D.C., leaving us the sole “conservative” voice on the court. Despite frequent disagreements over cases and issues, he always treated his colleagues on the court with the dignity and esteem owed to their high office. I know they admired and respected him for that. Even in our private discussions in his chambers, Justice Richardson was always discreet and reserved in his remarks about his colleagues. He was especially careful to preserve the sanctity of the events occurring in the conference room where the justices met each Wednesday to discuss and decide the fate of the leading cases of the day.

Once, after a particularly grueling conference, he emerged looking more worn and defeated than usual. I asked him what had happened, hoping for a full report. Instead, he simply shook his head resignedly, leaving me as usual to guess at what transpired behind those closed doors, and said, “Well, all I can say is, it’s no Sunday school in there.”

I can give you a good example of the effect Justice Richardson had on those who knew and admired him. One of his former staff attorneys, a practicing lawyer who is in the courtroom today, recently told me that in her law practice, when faced with difficult legal or ethical choices, she often would ask herself, “What would the Judge have done? Would he have done it that way?” And viewing the situation in that light, her choices were made easier. I could only agree with her, having gone through similar difficult situations myself_mainly in poker games.

I have many fond memories of Justice Richardson, but my favorite was also, sadly, my last. Perhaps some of you remember it too. Scores of us had gathered together in 1998 at a very special occasion at the Sutter Club to honor Justice Richardson with our blessings and goodwill. After hearing countless speeches from family, friends, and acquaintances drawn from each aspect of his busy and productive life, he took over the microphone, and briefly yet graciously thanked us all for coming. Then, to the astonishment and delight of us all, he extracted a harmonica from his pocket and treated us to a lively version of “Turkey in the Straw” at least I think that was it. He brought down the house.

How can any of us have a warmer memory of this extraordinary man?

Thank you.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Thank you very much, Graham. I now would like to introduce Mr. Paul Richardson, son of Justice Richardson, and a prominent lawyer here in Sacramento.

MR. PAUL RICHARDSON: Mr. Chief Justice and Honorable Associate Justices of the California Supreme Court: On behalf of the Richardson family I would like to thank you for taking the time this morning to honor my father, Justice Frank Kellogg Richardson. Dad always considered it a great privilege to serve on this court and to help resolve the important issues that serve to shape the law of this state.

Dad would want me to thank as well the entire Supreme Court “family”: the clerks, secretaries, bailiffs and attorney staff who were always helpful and kind to him in the nine years he was with you.

A special thank-you to Dad’s colleague and dear friend, Justice William P. Clark, Jr., for his presence and participation in today’s session. And a thank-you as well to Graham Campbell, Dad’s talented and loyal chief of staff.

There was an event in Dad’s life during World War II that was perhaps a signal that his career in the law would be anything but ordinary. When my father arrived in London in 1944 he was a second lieutenant in Army Intelligence. He was being assigned to Bletchley Park, north of London, which housed the top secret “ULTRA Project”, which had successfully broken German encryption codes. Dad learned that Prime Minister Winston Churchill was returning to England and was scheduled to address the British Parliament on the status of the war effort in the Balkans.

On the day of Churchill’s speech, Dad, in uniform, presented himself at one of the points of entry with identification papers he’d received from the U.S. Embassy. After being turned away at numerous secuity points, Dad finally convinced one guard to let him enter. Once inside he found multiple layers of additional security, but quietly and persistently, not taking “no” for an answer, Dad talked his way through different checkpoints until the last security guard finally relented and then proceeded to escort Dad to a lone empty chair next to a man in clerical garb within 30 feet of the speaker’s rostrum.

As Dad listened excitedly to Churchill’s oration that day, certainly someone in that hallowed chamber must have wondered, “Who is that American G.I. seated in the Distinguished Visitors gallery next to the Archbishop of Canterbury?”

I don’t know what that event says about the military security that day in London 56 years ago, but it said a great deal about the quiet persistence, sincerity, and ingenuity of my father, personality traits that would serve him well later on, in his chosen profession.

My father was the first in his family to chose a career in the law. His father was a Methodist minister from the midwest. His mother was the daughter of a pioneer Placer County rancher and Civil War veteran, who, as a Wisconsin farm boy, had fought under General Grant in battles down along the Mississippi and in the long siege at Vicksburg.

From this beloved grandfather, Captain George D. Kellogg, Dad learned of the sacrifice of war and the meaning of the words “duty, honor, and country.” It was also from him that Dad learned to venerate the memory of Abraham Lincoln, and it was this veneration of Lincoln’s life and career that inspired Dad to follow Lincoln’s path in the law.

My father was educated in public schools in Sacramento and San Jose. He graduated from Germantown High School in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Each summer in high school Dad journeyed back across the country by train to work in the packing houses and fruit sheds in Newcastle, Placer County. Those long train trips helped deepen Dad’s love of the American West with its rugged terrain, its varied climate and its colorful history. Dad was an inveterate Westerner all his life, and a proud Californian to his core.

After his freshman year at the University of Pennslyvania, Dad transferred to Stanford University where he graduated with distinction in political science in 1935, was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa Society, and then graduated from Stanford Law School in 1938.

Finding employment in the late Depression was no easy matter. But after a diligent search. Dad finally landed a position sharing office space with retired Butte County Judge Hirman Gregory.

Many years later in a commencement address at McGeorge School of Law, Dad described the start of his career in this way: “If you will forgive just a brief personal experience, it was 36 years ago that fresh out of law school I hung out my shingle to practice law on the second floor over a clothing store on a side street in Oroville. I recall vividly the thrill that many of you may experience shortly of studying the newly painted sign bearing my name over the title ‘Attorney at Law.’ I studied it from all angles, each one seemed better than the one before. It quickly became obvious, however, that I was one of the very few people in Oroville who noticed that sign and I hope that you will not have to wait as long as I did to earn the fees to pay for it.”

It was a humble start, but a start nonetheless. Clients were scarce, but Dad used his time constructively by immersing himself in the civic life of Oroville. He even entered the political arena by challenging an incumbent Assemblyman after living in the district all of nine months.

Dad’s greatest triumph in Oroville in those years, however, was the successful courtship of my mother, whom Dad spotted with her family while working as an usher at the local Methodist church. Their marriage lasted over 56_ years, and their loyalty, love and care for one another was obvious, no more so than in the last two years of my father’s life.

After his service in World War II, like many in his generation, Dad returned to the home front anxious to make up for lost time. He was 31 years old and married with one son. Dad and Mom made a pivotal decision at that time to relocate to Sacramento, a place where Dad thought there might be greater opportunities for advancement.

For my father, the years 1946 to 1971 could best be described as nothing less than frenetic. His law practice simply took off. After two years as an associate in the law offices of Sumner Mering, Dad went out on his own, preferring the life of the sole practitioner and the opportunity, as he put it, “to call his own shots.”

Dad developed a substantial civil practice. By all accounts he was a skilled and tenacious litigator, trying all manner of personal injury cases both on the side of the plaintiff as well as the defense. Juries found him intelligent, sincere, energetic and fair. He was honest and straightfoward. In the courtroom Dad knew what he was doing and he could be very persuasive.

My father was a careful craftsman of contracts and other documents. He always emphasized clarity in expression, and his writing, then and later, was usually devoid of much underbrush. As time wore on, however, the bulk of Dad’s time was devoted to probate work.

A prominent Sacramento attorney once told me that Dad was one of the last great general practitioners. He could do it it all, and he did it by himself.

Dad told me once that the greatest professional satisfaction he had experienced in the law was his years in private practice, for he had always enjoyed the interaction with clients, and the opportunity to help them and to advocate on their behalf.

As if the demands of his practice were not enough, Dad in those years also taught night classes in evidence and torts at McGeorge School of Law. He was also deeply involved in local and state bar matters, and in all manner of civic and community activities in the greater Sacramento region.

Dad traveled extensively to Africa, Asia, Northern Europe, Russia and the Antarctic. He always traveled with a purpose, seeking out social, religious, and political leaders in the host countries and then reporting back to local community groups his thoughts about the state of affairs in that region of the world he had visited.

As active as he was in professional and civic life, in his private life at home, Dad always had the allegiance and affections of his four sons, all of whom loved and respected him greatly. I have memories of his reading us Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer. He taught us to love the mountains, the outdoors, and our western heritage. His curious and engaging mind encouraged us to learn, explore and travel. In football games in the front yard we also learned that our father was very stubborn. It seemed that always, however desperate his offensive position on the field, when fourth down rolled around, on the question of whether to punt, he invariably replied, definantly, “We never punt” or “Never say die.” We would tell him that he was “dreaming,” and then brace ourselves for the Hail Mary pass or the deep crossing pattern we knew was coming.

Dad taught us to much by his example. That great athlete/philosopher Yogi Berra once said, “Sometimes you can observe a lot just by watching.” And what we saw when we watched our father was a man who was kind and generous, by nature self-contained, quiet in his person, humble in his manner, confident in his powers, and firm in his convictions. He was deeply religious, and he could also be very funny.

In 1971 Governor Ronald Reagan appointed Dad Presiding Justice of the Third District Court of Appeal. He was 57 years old. Three years later Governor Reagan elevated him to the California Supreme Court.

Dad believed that one of the strengths he brought to the bench and to the deliberations of this court was the experience he’d gained from 30 years in private practice. That experience provided him with a wealth of practical knowledge in certain procedural and substantive areas of the law, but it also gave him a balance and perspective and judgment about what was appropriate, and the practical effect certain decisions would have on practitioners in the trenches.

One of the things Dad enjoyed the most when he was on the court was the periodic opportunity he had to address groups of lawyers – young lawyers in particular: those just getting started. I think it reminded him of his own start in Oroville those many years ago. As a general rule my father was not inclined to offer unsolicited advice. He was always mindful of the unintended message contained in the remarks of the 12-year old school boy, who, when asked to write an essay on Socrates, wrote: “Socrates was a Greek philosopher who went around giving people advice. They poisoned him.” To these young lawyers Dad would offer up the following lessons that he believed had been important for him to know in his own career in the law, and those were:

That the practice of the law is a profession, not a business or a calling – profession with a noble and ancient heritage that has served to advance civilization and promote the cause of human freedom.

That the profession is governed by a rigid code of ethical conduct the rules of which each lawyer should read, study and internalize until they become a part of a lawyer’s life.

That one’s client’s interests must always supercede one’s own – ALWAYS!

And finally, that the most valuable asset a lawyer can ever accumulate is one’s reputation — one’s good name. And on this subject Dad liked the words of the great Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, who wrote many years ago:

“The highest reward that can come to a lawyer is the esteem of his professional brethren. That esteem is won in unique conditions and proceeds from an impartial judgment of professional rivals. It cannot be purchased. It cannot be artifically created. It cannot be gained by artifice or contrivance to attract public attention. It is not measured by pecuniary gains. It is an esteem which is born in sharp conflicts and thrives despite conflicting interests. It is an esteem commanded solely by integrity of character and by brains and skill in the honorable performance of professional duty. . . . In a world of imperfect humans, the faults of human clay are always manifest. The special temptations and tests of lawyers are obvious enough. But, considering trial and error, success and defeat, the bar slowly makes its estimate, and the memory of the careers which it approves are at once its most precious heritage and an important safeguard of the interests of society so largely in the keeping of the profession of the law in its manifold services.”

My father could not have known, when his journey in the law began, how far, or along what path, his career would take him. But Dad set his standards high, and he kept them there, and he pursued his career with energy, intelligence and integrity, and in so doing, in this way, he brought honor to himself, his family, his community, and his profession.

Thank you very much.

CHIEF JUSTICE GEORGE: Thank you very much, Mr. Richardson.

I want to thank again all those who have contributed their special and memorable remarks to this morning’s memorial session.

In accordance with our custom, it is ordered that the proceedings at this memorial session be spread in full upon the minutes of the Supreme Court and published in the Official Reports of the opinions of this court, and that a copy of these proceedings be sent to Justice Richardson’s family.

(Derived from Supreme Court minutes and 22 Cal.4th.)